|

Railroad Rules and Regulations: PDF's

When we talk of "the rules", we usually are alluding to "operating rules", the rules that "rails" (operating employees) follow to get the trains safely over the road. But on any large railroad, the numbers of operating department trainmen, enginemen, towermen, dispatchers and the like are typically dwarfed by the droves of employees who work in dozens of other departments. They require governance, as well. And then there are union work rules (a.k.a., "the agreements"), industry standards and state / federal laws and regulations with which to contend. Likewise, the organizations responsible for these have their own sets of rules.

These codified standards, bordering on micro-management at times, closely follow the military model out of original and present necessity. Railroads were the first corporations and the first private businesses to hire hundreds and then thousands of employees in an age when a "large" business employed a few dozen. For tips on how to organize a huge number of mobile, geographically spread-out people, railroad managers really had nowhere to look beyond their own nation's army. In terms of dealing with complicated logistics and organizing legions of people,this turned out to be a pretty good match. In terms of governance and discipline of civilian employees, not so much.

Below you shall find PDF files scanned by Wx4 and generous contributors, as well as some links to rule books that can be found elsewhere. Wx4 invites you forward your favorite rule book scans for placement on this page.

Note: In late July, 2020, this page has begun to see a large influx of new material from "seabass", one of our two incognito ex train dispatchers along with Englewood. Note: In late July, 2020, this page has begun to see a large influx of new material from "seabass", one of our two incognito ex train dispatchers along with Englewood.

Primevil Rules: before the Standard Code

Standard Code of the American Railway Association

American Railroads underwent tremendous technological changes during the first part of the Twentieth Century on a level not seen before, or since. This collection of known online Standard Codes of the period serves as a chronicle of how these changes affected operations.

- 1890-04-01 SP Atlantic System / others - Wx4

- 1897 - Internet Archive

- 1905 - Rule Book of the American Railway Association - Omnibus book of rules for all departments; includes Standard Code - Google

- 1906 - Google

- 1906 Standard Cipher Code - Internet Archive - 751 pages!!!

- 1911 - Google

- 1915 - Google

- 1918-10-30 New York Central / USRA - uses 1915-11-17 Std. mmmCode; note the colorful clearance cards on pp. 78-79 - Wx4

- 1938, as revised through 1951 - Jon Habegger

- 1949 - Jon Habegger

Consolidated Code of Operating Rules

The following scans are courtesy Jon Habegger.

- 1939 - for MILW, GN, NP, SP&S, UP NW District

- 1945 - for MILW, DSS&A, Mineral Range, GN, MStP&SStM, NP, Spokane Int'l., SP&S, UP

- 1959 - for MILW, DRI&NW, Des Moines Union, DSS&A, GN, M&St.L, MN&S, MStP&SStM, MN Transfer, St. Paul Union, NP, SP&S, UP Oregon Division

- 1959 - Catechism on the Consolidated Code - Q & A's about the code designed to prepare employees for exams

Uniform Code of Operating Rules

Miscellaneous Railroads (Southern Pacific - bottom right column)

The following are Wx4 scans, except as noted.

Operating Rules, Regulations & Instructions

- 1890-95, circa Davenport & Rock Island Ry. Rules & Regs. for

Conductors & Motormen - street car line predecssor to DRI&NW - seabass

- 1891 Old Colony RR (absorbed by New Haven RR, 1893); includes color map from 1889 Annual Report

- 1900-12-16 DL&W ABS & interlocking signals ins. - seabass

- 1901 Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis rules; note missing pages enumerated on cover

- 1903-10 Lake Shore & Michigan Southern

- 1903-03-01 Philadelphia & Reading

- 1904-01-00 Vandalia RR Telegraph Block System Rules - seabass

- 1909-05-01 Louisville & Nashville

- 1916 New Haven / Central New England maint. of way rules

- 1918-10-30 New York Central / U. S. Railroad Administration

- 1922-10-15 Dallas Railway rules - seabass

- 1923-05-01 Chicago Great Western - Google Books

- 1926, circa IC Q&A re subrban car MU operation - probably issued when cars were introduced in 1926 - seabass

- 1929 Canadian National and subsidiaries

- 1930-03-15 Yosemite Valley Railroad rules

- 1931-11-29 Alton Railroad Co. - instructions for manual block opperations

between Ft. Wayne Jct. & Chicago Terminal - seabass

- 1933-01 Wabash & NKP Joint CTC, Walbridge-Warnick Jcts. - seabass

- 1936-01-01 Southern Illinois & Missouri Bridge Co. - Jon Habegger

- Chicago Union Station - Jon Habegger

- Union Pacific

- 1940-11-01 CRI&P instructions to UCOR train order operators - seabass

- 1942-01-15 NKP operation of trains in CTC - seabass

- 1944-09-01 Belt Railroad Company of Chicago - Englewood

- 1945-06-01 K&IT REM CTRL switches, signals rules - seabass

- 1945-12-01 St. Paul Union Depot - seabass

- 1946-01-01 Chicago, South Shore & South Bend instructions for operating

on IC - seabass

- 1946-10-15 Jersey Cental Instr. Governing Signalmen -seabass

- 1947-08-01 Dallas Union Terminal Operating Rules

- 1947-09-01 ACL signal aspects & indications rules - seabass

- 1948-04-01 B&O / B&O ChicagoTerminal instructions for operating over bridges "Provided the Bridges Are In Good Physical Condition, and So Maintained" - seabass

- 1950-01-01 Los Angeles Jct. Ry. rules - seabass

- 1950-07-01 NKP rules gov. use of M/W track cars - seabass

- 1952-01-01 Lake Terminal Railroad - seabass

- 1953-06-01 Erie RR Instructions for Passenger Conductors - seabass

- 1954-01-01Aberdeen And Rockfish rules - seabass

- 1956-11-01 Detroit Terminal rules - seabass

- 1957-04-28 NYC Instr. for Operators (Signamen) - seabass

- 1957-07-01 Rules & Instructions for Conductors Suburban Collectors & Train Baggagemen 78 pgs.! - Jon Habegger

- 1961-12-22 Cuyahoga Valley rules - seabass

- 1962-09-01 Denver Union Terminal rules - Moore

- 1965-10-01 D&RGW - courtesy Bob Webber & Jon Habegger

- 1964-05-01 Lake Superior & Ishpeming - Jon Habegger

- 1971-02-01 Potomac Yard, B&O, C&O, PC, RF&P, SRR joint rules - seabass

- (1971-04-01 Bessemer & Lake Erie rules - seabass

- 1972-01-01 East Erie Comercial Railroad - seabass

- 1980 Illinois Central Gulf Rules for Train Dispatchers

- courtesy Mark Rickert

- 1981-05-00 Chessie Understanding Restricted Proceed - rules pamphlet - some RRs called this signal indication "restricting"; Note: US RRs repeatedly revisited Restricted Speed's particulars during this era. seabass

- 1977-02-15 Erie Mining Co. rules - seabass

- 1980-03-01 Los Angeles Junction Ry. rules - seabass

- 1982-11-15 Amherst Railroad rules - seabass

- 1985 BC Rail Electrified Territory Rules and Ins. - seabass

- 1988-05-20 Sabine River & Northern rules - seabass

Air Brake & Train Handling Rules

Other Rules

|

|

NEW 3-18-25

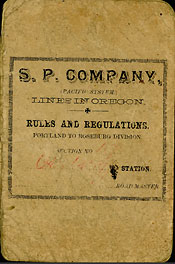

1888 SP Portland to Roseburg Division Instructions to Sectionmen

"An untidy section will be considered evidence of the foreman's incompetency."

One of this book's interesting aspects is that it was addressed to a single division. It also is the earliest SPMW rule book that we have yet seen. - Wx4 Collection

|

NEW 8-14-25

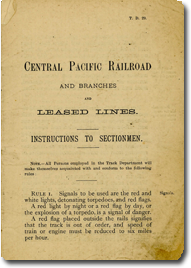

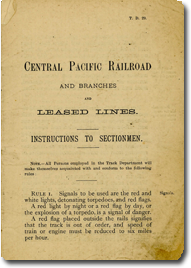

(undated) Central Pacific Instructions to Sectionmen

Staff is unsure of when this 11 page booklet appeared. It's content is identical to the SP booklet above, but formatting varies between the two. It was printed under the auspices of W. G. Curtis, Superintendent of Track.

Online records at California State Museum tell us this about Curtis:

|

|

In 1891, the Southern Pacific Track Department and Bridges & Buildings Department were combined to form the Maintenance of Way Department. Since the Track Department was the senior department, then former Track Department head W.G. Curtis became the Engineer, Maintenance of Way and Arthur Brown, who was the Superintendent of Bridges & Buildings, became Assistant Engineer. In 1892, Brown retired and W.G. Curtis was awarded a new job title: Engineer, Assistant to General Manager and Engineer Maintenance of Way. In 1902, J. H. Wallace replaced Curtis.

We easily conclude that this booklet appeared before Curtis's appointment as Engineer, Maintenance of Way in 1891, but exactly when? Perhaps more telling about its publication date is the existence of a nearly identical book put out in 1888, -SP Portland to Roseburg Division Instructions to Sectionmen. There is, however just enough formatting difference between the two to suggest that they were published at different times, but not too far apart. Content-wise, they are identical.

Thus we would say that the booklet dates pretty darn close to 1888. Given their identical content, why there was not a less expensive omnibus book for all SP holdings is interesting to contemplate.

|

|

|

|

Maps & Timetables Pages

last additions: 8-14-25,

1-13=26m

Wx4's take on:

The History of American Railroad Operating Rule Books

Kid, you've got to learn the rules so you'll know which ones you're violating.

- SP engineer of unrecalled identity speaking to author one night in 1978.

Southern Pacific Rule 108: In the case of doubt or uncertainty, the safe course must be taken.

Southern Pacific (unofficial) Rule 108-A (circa 1980): When in danger, or in doubt, run around and scream and shout.

During railroading's first days, there likely were very few, if any, written rules, since railroad rules - the operating ones, anyway - have traditionally come into being in the remedial wake of some disaster or another. Since railways were a totally new technology, nobody could thoroughly predict what potential calamities lay ahead when something new was introduced. In those early times, "the rules" were more spur-of-the-moment, word-of-mouth sendoffs of conventional wisdom, "Good luck boys! Don't forget to slow down for curves - you remember what happened last week - and, for God's sake, stay sober."

This arrangement was fine until it was time to complicate things with a second train. This opened the can of worms, because getting multiple trains around each other turned out to be the most complicated part of railroading. Some outfits tried operation by "smoke signals", whereby two opposing trains simply looked out for each other. On a clear day, when the birds were singing, this was all well and good, but on a dark, gloomy day, especially when a crew had been amply warming itself with liquid consumables, certain flaws became crushingly apparent.

Timetables, the original rules references in print, theoretically cured the problem of unexpected encounters by posting schedules for trains to be respected by each other. Later, timetables began to show specific meeting points, and the resultant frequency of inordinately long waits in sidings quickly brought on a realization of just how breakdown-prone trains actually were. Timetables were consequently amended with various codicils addressing what to do in these situations - most of them helpful, homely instructions, roughly akin to, "Should your train break down on Bull Hill, secure the use of a good horse (not a mule!) to ride out and alert the other train to proceed."

Those sorts of rules were generally effective (and their class survives today in the form of special rules or instructions particular to specific locations) as long as railroads were no longer than a convenient horse ride. But as lines lengthened, branches were added and trains grew in size, speed and frequency, the sheer quantity of new-rules-born-of-mistakes caused some timetables to be a double-sided yard long. Boston and Providence Railroad already had 14 rules adhering to the margins of its timetables in 1835, and the essentials of several of them have survived into modern times.

Just exactly when the first book of rules apart from a timetable appeared in the U. S., we don't know. About 90 years ago, Railway Age published what they maintained was the earliest rule book that they had heard of, a 3.5 x 5.5 inch booklet issued by the Western Rail Road in 1842, which included all of 13 rules within its modest 18 pages (see PDF's). This may actually not be the earliest one, but it must be close at the very least. The earliest scanned American timetable that Wx4 has located online is an 1854 example from Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore. Interestingly, Wx4 has also found three rule books from 1840's English Railways online. It might be reasonable to assume that the Brits came out with books earlier than Americans, since they began running trains earlier, and their railway infrastructure was much superior to ours.

Researchers of the period conclude that rule books did not come into widespread domestic use until the early 1870's, which at first seems odd, given that the great boon to railroading, telegraphic train orders, had already been in existence for two decades. Train order and associated rules would soon cause rule books to bulge, but in the meantime, railroads - being conservative and at times dunderhead institutions - were slow to adopt this revolutionary technology. Likewise many of those that did adopt train orders failed to include references to them in their books of rules or timetables, though it is fairly likely that dispatchers had published guidelines to draw upon. By the 1870's use of telegraphic train orders had become common, and a little later in the century, nearly universal. It may be that the growing complexity of the system, meaning the growing profusion of related rules may have been the precipitating cause for adopting rule books. Like train orders, rule books were nearly universal by the 1880's.

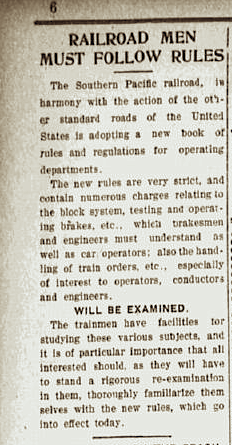

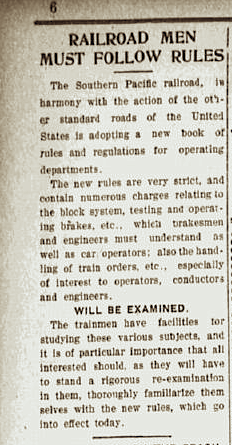

(image at right) In 1903, SP issued a new book of rules that revised its 1898 edition. Control of the railroad passed from Huntington to Harriman in 1901, and by 1903, the latter was well on his way to modernize the railroad and its operations. As it was, at the time of the new book, his railroad was still a wreck waiting to happen. Evening news, San Jose, 8-1-1903, p. 6

A nagging question: When did the first CP and SP rule books appear?

SP Lines East adopted the Standard Code in 1887, but Lines West did not, and appeared to have continued (maybe Lines East, too?) placing the rules in timetables until the early 1890's. The first SP book that Wx4 knows of was the 1892 edition. Was this indeed the first?

|

Consequently, by the 1880's, the nation's railroads annually hosted an appalling number of "pile-ups", and literally thousands of people died each year on the trains or along the rights-of-way. Technology, or more accurately, the improper implementation and poor maintenance thereof, by now was clearly advancing at a rate beyond any individual railroad's ability to totally keep up with its fallout. This occasioned professional organizations to come into increasing favor as means to address industry-wide issues. The Master Car Builders Association, for one, began to tighten-up equipment standards, which was a significant help, because, using today's hindsight, some equipment and appliances apparently were manufactured with the aim of causing derailments and / or injuries. On the operating side, the American Railroad Association used its collective wisdom to come out with a Standard Code of Train Rules in 1887.

This all was advisory (Federal Government's mandates were still a decade away), railroads were free to adopt the Standard Code either in bits and pieces, or as a whole, and the largest railroads generally tended to go with the former, smaller roads, the latter. Southern Pacific was a bit schizophrenic in its reaction to the new code. SP's Atlantic Lines adopted it, while the Pacific lines, as best as can be determined, continued to forsake the book of operating rules concept until at least the early 1890's.

|

| The Standard Code, along with later competing Consolidated Code (Northwestern railroads) and Uniform Code (Midwest Railroads), had a good run. It only was replaced en masse by the succeeding General Code of Operating Rules in 1985. Several roads instead decided to opt out and formed the Northeast Operating Rules Advisory Committee (NORAC), which came out with its own version of the rules two years later.

Since then, the Federal government has gradually and abundantly insinuated itself into "the rules", generally for the better, through the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 049. Positive Train Control will likely be the central focus of rules debate in the near future, as the unforeseen consequences of unproven technology collide head-on with the real world. That's the way it's always been.

- E. O. - January, 2019

An interesting and somewhat less light-hearted rules history entitled "Early Rules and the Standard Code" appeared in the October, 1939 issue (no. 50) of The Railway and Historical Society Bulletin. It is available for free online perusal at JSTOR.

|

Outside Organizations: govt., unions & agreements, associations, etc.

Southern Pacific, Central Pacific & Subsidiaries

Wx4 scans; outside links to other known complete SP books, as noted

Operating Rules

Maintenance of Way Rules

Air Brake Rules

Other Rules

|