|

mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmShortlines Index

mmmmmmmmmWhy would they buy a 44-Tonner, of all things?...

mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmAn Amador Central Interlude

|

|

|

Back in August, 1969, as the family and I were returning from a vacation in the Sierra Nevadas, we encountered Amador Central General Electric 44-Tonner #8 trepidaciously descending the grade along Highway 49 between Martel and its Southern Pacific connection at Ione.

Amador Central depended upon this tiny engine to propell its trains in heavy grade territory for nearly two decades, and a few other California shortlines likewise employed 44-Tonners on steep profiles, as well. At the time, I was a bit perplexed as to why this was so, given the diminutive dimensions of these locos. At any rate, #8's time was about done. A Baldwin switcher was on the property, but it had initially proved to be too heavy for the infrastructure, so #8 was making a brief curtain call while AC propped-up bridges and replaced ties at rail joints here and there. My brief interlude photographing AC came at a moment of luck.

When I posted some of these photos on TrainOrders.com recently, I found that others fans were equally perplexed about #8: Why would they buy a 44-tonner, of all things? This led to an intriguing conversation about AC's operations and motive power requirements. Jeff Moore, one the deans of current western shortline historians, weighed-in with a very convincing argument in the favor of AC's decision to replace its elderly 2-6-2 with #8: Simply the little diesel could pull more!

While we're at it, I want to plug Jeff's new (2016) book, California's Lumber Shortline Railroads (Foothill Media). Jeff takes a fresh approach towards backwoods shortline railroading in California by separating the common carrier lumber haulers from their benefactors, the lumber mills and logging railroads that supplied them. His work is both an insightful look at this railroad genre, as well as the individual companies. One of the great things for me about the book is that Jeff brings the story up to the present day. My knowledge of these lines pretty well remained in a state of suspended animation after reading 1960's and 1970's copies of Western Railroader and Pacific News. And yes, there's roster data to satisfy you loco-centric railfan. Buy it - you'll like it!

|

Excerpts from TrainOrders.com:

Driving back home from an aborted Colorado trip a couple of days ago (don't ask!), I noted that the rickety rails of the abandoned

Amador Central RR are still in place along Highway 88 in California's Sierra foothills . See Jeff Moore's fine, new California's Lumber

Shortlines (plug, plug) for up-to-date info on the line.

No, I didn't stop to take photos (don't ask!) but when I returned home, the sighting prompted me to dig into my old negatives for the

photos I took of AC in August, 1969. After having the negs (poorly) developed at the local Rexall Drug Store soon after I shot them, I

never made a print, because it was "obvious" to me that they were a disaster. I photographed them with my "big mistake", an East

German 35mm Exacta camera, which featured a very soft lens and soon developed light leaks. Compounding that, I took my

telephoto shots (the first ones that I ever tried) using a Vivitar lens with a doubler. Whatever minimal quality that the Vivitar had was

negated by the doubler, plus another mistake: grainy Tri-X film.

But, all is not lost, for through the wonders of Photoshop, I was able to compensate for past errors... somewhat. They still are a bit

blurry and have the slight appearance of dirty bath water, but they are reasonably acceptable, I'd say. -EO

- Evan Werkema:

Always been amazed that a 44-tonner was evidently enough locomotive for that railroad for many years.

- Me:

I was thinking that as I drove along Highway 88 the other day. Though it's generally a downhill coast for the loads, I noted what

appeared to be a short stretch of very steep uphill. One wonders how much of a 'run-for-the-hill' you'd get out of a 44 tonner.

Plugging Jeff's book again, he says that #8 was good for four or five empties on the uphill, presumably when it was in its prime. It

seems like the trains must have not only been subjected to curve-bind, but 'generally-misaligned-rail-bind' as well. By the time of my

photos, AC also had a Baldwin switcher, so I was surprised to see the 44 tonner running (at age 24). Kinda makes me think that the

Rock Island wasn't all that crazy for employing 44 tonners and other small critters out there on the Plains flatlands.

- Lee Hower:

This a question that I have been pondering, how so many of our Sierra lumber roads started out with 44 Ton GE diesels where they

had grades to contend with and heavy loaded cars, whether upgrade or downgrade: Almanor Railroad, Quincy Railroad, Camino

Placerville and Lake Tahoe, Amador Central. That GE salesman did a heck of a job in California! But you'd think they'd opt for

something a little beefier, at least up to the level of a GE 70Ton that Almanor eventually went to, sending their 44Tom to an affiliated

road in Oregon. And now, the only road of those four still in existence, the 4 mile Quincy Railroad, runs with two 1200hp EMD

switchers. All on a railroad that has all of four switches outside of the UP interchange at Quincy Junction!

- callum_out:

There's that crossing on 88 which I'm sure you're referencing where the train goes from stopped to cool

the brakes, across the road and immediately up a short incline. They were slow across the crossing to

make sure it was clear and than wide open for about twenty seconds. The Baldwins would really chug

hard for a few seconds before getting the loads up and over that spot. Been a whole lot more interesting

with that 44 tonner. Those were excellent shots, you see so few with the 44 and as for Martell, last few

years it was well into falling down!

continued below the photos continued below the photos

|

|

|

|

|

|

left - at an unknown crossing, perhaps Beaver Loop Road

above - why a 44-Tonner, instead of an RS-2; Today, twelve years after Amador Foothills Railroad (the railroad's final apparition that came after the Amador Central ceased business) gave up the ghost - the still-extant tracks look the same, no better, no worse. |

|

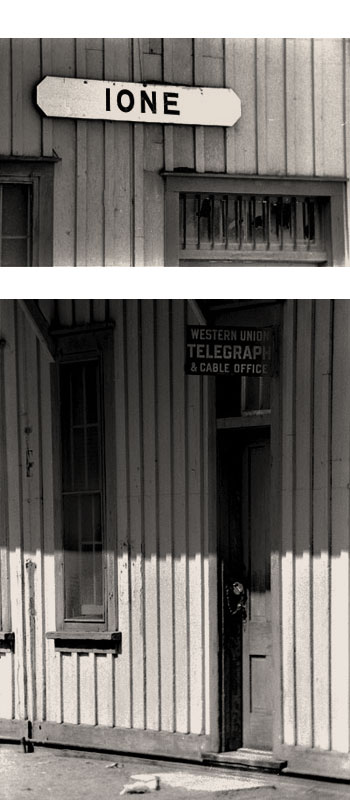

Southern Pacific's Ione depot and joint yard - Though it's thoroughly disheveled appearance here suggests that it was in its final days, in 2013 it was moved off of UP property to City of Ione land for restoration. In 2010 Sierra Pacific Industries sold the railroad itself for $1.00 to both Amador County Historical Society (ACHS) and Recreational Railroad Coalition Inc. Amador County Historic Railroad Foundation is currently raising funds to acquire Baldwin S-12 #10 (ex T&NO #105; SP #2121). AC's depot at Martell burned in 2012.

|

|

|

|

|

Amador Central's big bridge and trestle over Highway 88 - Today it is more bridge and less trestle. Note the rails leaning on the trestle, an apparent effort to add a little stability to the structure. |

|

|

|

Iron Ivan, 2-6-2 #7 - The loco came from McCloud River (#8) in 1939. This was the loco (along with two others of uncertain running status) that #8 replaced in 1945. There presently are no concrete plans to restore her to service, as far as I know. She now has a roof over her head, however.

below, Amador Central excursion in May, 1948 - Though "retired", she was still in good enough condition to pull a train. (photographer unknown, Wx4 Collection) |

below, Amador Central Baldwin #9 seen here at Martel in May, 1973 was waiting in the wings when I recorded the photos of 44-Ton #8.

|

continued from top continued from top

- Me:

Yeah, it is a bit of a puzzle, Lee, especially since the orignal selling point was the elimination of firemen under the 90,000 pound rule.

The rule would not have applied to these railroads, since none of their engineers were union represented, as far as I know (I could be

very wrong on this). I guess that it all boiled down to locomotive capacity as a function of expected traffic. AC crews typically took

about four hours for a roundtrip between Martell and Ione (again quoting Jeff's book), so two round trips would have involved minimal

overtime, and at least three round trips under the 16 hour law was quite practical when need be. Initial low cost for a gutsy little

locomotive must have held sway over the prospect of occasional crew overtime costs. Likewise, I suspect that 44 tonners'

maintenance costs were much less than heavier locomotives, thus likely ameliorating the impact of crew overtime costs to some

unknown extent. That's my guess, anyway.

- Jeff Moore:

There are several factors that cross my mind that made the 44-tonner ideal for a lot of the California shortlines.

1. Tractive effort. Now, I won't pretend that I completely understand everything about this subject...but the 44-ton had a starting

tractive effort of 27,000 pounds (continuous tractive effort of 12,400 pounds at 12 miles per hour). The Amador Central #7 (former

McCloud River #8), the steam locomotive the AMC #8 replaced, had a tractive effort of but 19,000 pounds. The #7 weighed 107,000

pounds, while the 44-tonner weighed in at something less than 90,000 pounds. In practice, at least on the AMC, the GE diesel

produced 8,000 pounds more TE from less weight than the steam locomotive it replaced. The TE difference would not have been as

favorable on the Camino Placerville & Lake Tahoe, as a three truck Shay tended to have TEs in the 30,000-40,000 range. In the case

of the California shortlines, the 44-tonner's low horsepower rating was not a substantial issue, as very few of them had the need to

run at speeds that would have significantly taxed the otherwise low horsepower rating of this locomotive.

2. Track work. Keep in mind most of these California shortlines had lots of light rail, questionable trackwork, and sharp curves, all of

which lent themselves nicely to the 44-tonner against other available options. Keep in mind those roads that did buy the 44-tonner

and then much later went to larger power (such as AMC) typically had to completly rework and upgrade their track structures to

accommodate the larger power.

3. Freight car sizes. At the time of introduction, the 44-tonner entered a world still filled with 40-foot, 40-ton capacity freight cars.

The trackwork done later in time to allow for the operation of larger power generally coincided with track upgrades that would have

been required anyway to handle heavier freight cars on all except for the CP<, which gave up rather than attempt to rebuild itself so

as to handle the larger equipment.

4. Adverse grades against loads. Of the various California lumber roads discussed, only the Almanor had extensive adverse grades

against loaded cars, and it's noteable that was the first of the roads to make the jump to larger power. I'm deliberately overlooking

the Quincy here, but they had a very short (but stiff) adverse grade, and so little other railroad that it didn't really matter how many

times they had to double their hill. Almost all of the other roads had loads downhill/empties uphill.

5. Purchase price. The 44-tonner could be had new for around $50,000, while the 70-tonner came in at a price point $15,000 or so

higher than that. GE could and did make exceptionally generous financing terms to potential buyers, and most of the railroads found

fuel, labor, and maintenance savings alone paid for the new diesels.

Despite the small size, the 44-tonner proved itself to be what these various shortlines required at the dawn of the diesel era. There

are almost certainly other factors I'm overlooking, but these are the ones that jump out at me as having the most to do with the

success of the small power on the California railroads.

- callum_out:

Most likely that CAT shop at the mill was familiar with the prime mover in the 44 tonner, that would be a big selling

feature. They were simple to operate, the braking system was familiar. Logging companies were like the oil patch people,

change often came with difficulty.

callum_out , elsewhere:

There's that crossing on 88 which I'm sure you're referencing where the train goes from stopped to cool

the brakes, across the road and immediately up a short incline. They were slow across the crossing to

make sure it was clear and than wide open for about twenty seconds. The Baldwins would really chug

hard for a few seconds before getting the loads up and over that spot. Been a whole lot more interesting

with that 44 tonner.

- SandingValve:

That location on the railroad was known as the 'Mountain Springs' crossing. Mountain Springs was just railroad east of the Highway 88

crossing. The actual railroad location where brakes were cooled on the downhill run and engine lubing (steam era) and traction motor

cooling (diesel era) on the uphill run, was known as 'Halfway House', located just railroad west of the the Mountain Springs railroad-

Highway 88 crossing.

TOP TOP

|

|

|

|