|

Taking Stock of William Jennings Holman and His Improbable Locomotive, Part 6

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Products of an overly inventive imagination

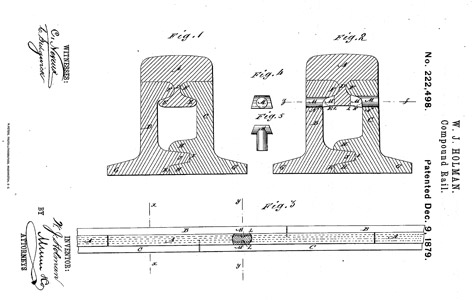

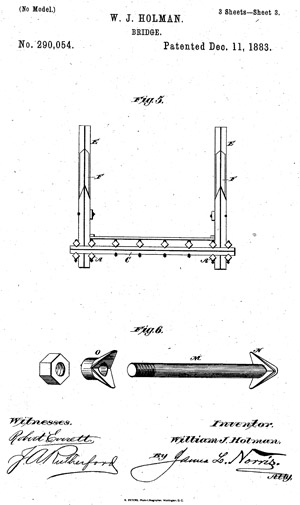

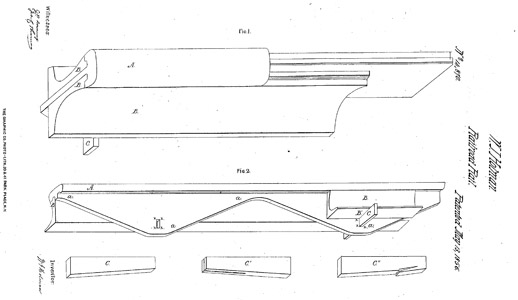

On the whole, Holman's moonshine schemes were too modest to attract a flood of attention, and those in-the-know tended to give his odd and suspicious activities a wide berth, the net result being that he had plenty of time on his hands to devote to his lifelong passion for inventing things. His fixation over compound rails never left him, and in 1879 the Patent Office awarded him a patent for new design that in no way resembled his oddball first attempt of 1856. This time around it resembled "U" rail, which had found more favor in the industry than compound rail, but had likewise failed to catch-on generally. Compound rail itself had completely fallen out of use by the end of the Civil War because of its primary bugaboo, a propensity for its binding nuts and bolts to work loose, causing the rail to fall apart. Holman now was certain that he had engineered a solution - three-part rails that "will require no other device, appliance, or attachment to make perfectly secure rails than to place them together and spike them to the cross ties." The inconvenient fact that locking pins had to be inserted into the rail to prevent horizontal creep escaped mention until a couple of paragraphs later. Whether it actually was a technical triumph or not did not matter much. It was if he had invented a revolutionary new type of buggy whip fifteen years into Model T production, and expected automobile owners to sit up and take notice due to its technical brilliance. What he did not grasp was that the horse was still dead. |

|

||||||||||||

|

compound rail patents: 1856, left and 1879 lower right |

|||||||||||||

|

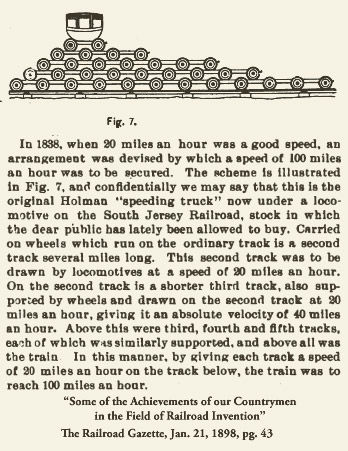

One man's flop is another's inspiration By this time, Holman's attentions were already diverted towards something that stirred his juices considerably more than a bridge. Earlier in the decade, a misguided fellow from Detroit named Eugene Fontaine had latched onto an idea that power transmission by "friction gearing" was a much more energy-efficient form of steam locomotive propulsion than the conventional arrangement of driving wheels. Friction gearing performed the same function as toothed gears, except that the mating surfaces were smooth, rather than cogged - think of an automobile transmission equipped with smooth "gears" that relies upon the mating friction between them to transmit power. For reasons hard to fathom now, Fontaine and fellow members of the scientific fringe were convinced that friction gearing was so efficient that, in the case of locomotives, track speed could be increased without a corresponding increase in engine power output. Mainstream scientists considered this as poppycock, because it violated their traditional (extant since mid-century) conceptual framework regarding the law of conservation of energy. According to the theory - first postulated at mid-century and refined into the First Law of Thermodynamics early in the next century - the quantity of heat consumed is proportional to the work done. This was a work-a-day assumption on the railroads. Heck, any locomotive engineer could tell you that his locomotive consumed more fuel and water in a given distance as its speed rose. |

|||||||||||||

One critic quipped that the Fontaine Locomotive appeared as if it had been compressed |

Fontaine was so smitten by the myth of friction gearing that, after first obtaining a patent, he set out to prove his theories in 1881 by ordering a pair of demonstration locomotives from Grant Locomotive Works. (see image) Their appearance was so peculiar that they immediately attracted a chorus of catcalls and a lot of head scratching. The friction drive consisted of two six foot wheels that received power from canted steam cylinders and transferred it to a set of much smaller single drivers which each had two rims, one which mated with the overhead wheel and the other with the rail. To make the setup even more "efficient'" he devised a manually operated lever to raise the larger wheels ever so slightly to increase "efficiency" even more by reducing friction. Some way, somehow, the intervening voodoo performed by the extra wheels was supposed to keep the power requirements from the cylinders relatively unchanged as speed increased. Expressed as an equation, his thinking is thus: energy + friction gearing = more energy. Holman's Law, we shall call it. His experiments conducted on Canada Southern railway showed that his locomotives could perform at high speeds comparable to conventional locomotives, but the traction provided by the single sets of drivers was so anemic that the locomotives were universally pronounced to be impractical, so much so that the topic of efficiency apparently never came up. Reaction to the results was swift and merciless. The Fontaine Locomotive was now Fontaine's Folly; Fontaine's Flop; Fontaine's Freak. After the brief round of trials, the locomotives sat idle until 1884, when they were converted into normal machines. |

||||||||||||

|

1890-1894: Exactly who was this guy Caldwell, anyway? |

|||||||||||||

|

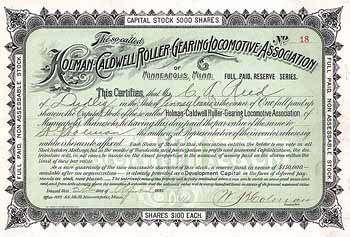

Late in life, Holman commented to a reporter that he initiated his development work on a friction-geared locomotive upon moving to Minneapolis in 1885. He never mentioned Fontaine's experiments, but it is reasonable to assume that he found inspiration where most people found disaster. Once he sidestepped the hurdle of immutable science to take up the panacea of friction-gearing, the matter was settled. From then-on he labored under the premise that technical design errors sealed Fontaine's fate. The theory was sound, he was sure, and it awaited a man of higher intellect to carry it to fruition. This is pretty much what one would expect from a confidence man. No hint that he was onto something appeared in the historical record for another five years, except that he occasionally turned up in Milwaukee hotels. If his brother-in-law was a part of Holman's initial ruminations is unknown, but he died in 1888, well before a design had surfaced in public. In 1890, Holman's thoughts were sufficiently solidified to place them in motion, so at mid-year he began selling stock. By now he also had a partner, an ex Minneapolis furniture factory machinist named Henry J. Caldwell. Almost nothing is known about Caldwell except that his former job would have given him a working knowledge of belt and pulley gear reduction*, plus he likely had journeyman level expertise as a lathe operator. These were critical skills, because Holman was contemplating a device that was nothing more than a two-tiered set of rollers to be placed underneath a conventional steam locomotive's driving wheels. Caldwell was tailor-made to convert concepts into physical reality and while Holman proceeded to scout little old ladies' parlors and cooks' rooming houses, the task of constructing a working model of the truck fell to him. |

|

||||||||||||

|

He could not see the forest for the trees, either.

|

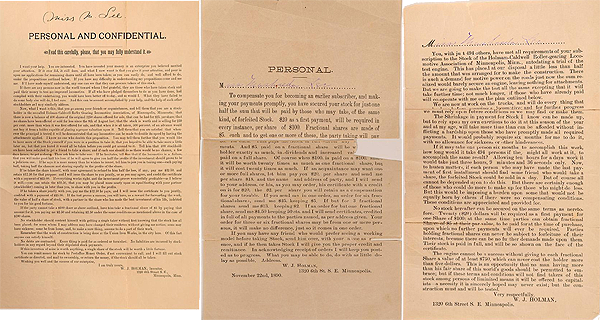

---top - This illegible image of a blank September, 1890 stock certificate, taken from |

||||||||||||

|

By November Caldwell had completed a miniature prototype of the truck. Holman sent out invitations to the undoubtedly anxious stockholders to "see a complete roller-geared locomotive working by steam power - a severe test and pronounced success" on the night of November 7th at what is presumed to have been a hotel ballroom located a couple of blocks from Chigago, Milwaukee & St. Paul's downtown depot. (the "General Office" was located in Holman's home across the river)

|

|

||||||||||||

Throughout his relationship with Caldwell, Holman had continually credited himself as inventor, so what was going on here? Did the reporters have their wires crossed, or did the news originate with Caldwell? Was he attempting to steal credit from his partner, or had Holman actually swiped concept from him? Or had they each contributed enough to be in fact co-inventors? These are the first of a large set of unanswered questions surrounding the Holman Locomotive. Whatever the case, Caldwell dropped off the face of the earth after the stories hit the streets. The company continued on as Holman-Caldwell for another five years, with or without Caldwell. The coffee table locomotive worked quite well enough for Holman to drop the small time local stuff in favor of a much larger audience. In early 1891, he sent out a press release for national circulation, knowing that editors had the habit of printing just about anything they were handed if they had a last-minute hole to fill. It read, in part: |

|||||||||||||

This was quite a move up for a fellow who, six months before, filled his time collecting two-dollar down payments on stock from household help. In truth, it was Holman drawing from his well-worn playbook. The grand plans were an attempt to scare additional prey out of the bushes, nothing more. The talk of patents was a hoax. His home was still his headquarters. Smoke and mirrors.

Casting a wider net brought in enough money to afford a full-size set of trucks sometime during the next three years. As things had unfolded, professional railroaders wanted no part of his crazy device, and in all liklihood, him as well. In the future, a host of differing concerns over the practicality of Holman's invention would surface, but for now and always, railroaders believed that running it at high speed was dangerous in the least, but more probably, suicidal - the darn thing would make a locomotive too top-heavy. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| This widely distributed photo is the only one known showing SOO Line #6 supported by the Holman-Caldwell trucks, as well as the original two story front truck arrangement. Note that the tender height has been nearly doubled to allow it to properly mate with the cab deck. Likewise, a different style Holman truck gives altitude to the lead end. The bearded old man at left is W.J. Holman, looking more like a circuit riding minster than a con man, but perhaps that was the idea. The young man next to him is believed to be one of his sons. The location is most likely is SOO's Shoreham Yard in Minneapolis. |

|||||||||||||

|

Despite the tests' limited circumstances, Holman had his shoe inside the reluctant industry's door. By September, he had coerced Northern Pacific to allow a trial at speed, something that they later regretted. The exhibition took place on NP's "B Line" southeast of Minneapolis on September 14. News coverage related that:

Holman's patently stupid antics petrified NP officials, who promptly dismissed him from their railroad. Soo Line managers likely witnessed Holman's high speed antics with chagrin, but with a measure of amusement over the discomfort of their cross-town rivals. They were kind enough to forgo an immediate rescue of engine #6 in favor of allowing it to accompany Holman's creation for display at the Minnesota State Fair, no doubt under the proviso that it be a static display. |

|||||||||||||

|

CHANGE!

|

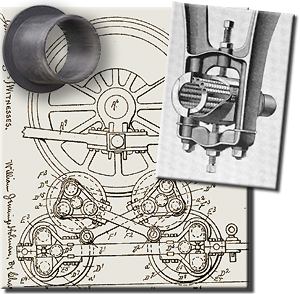

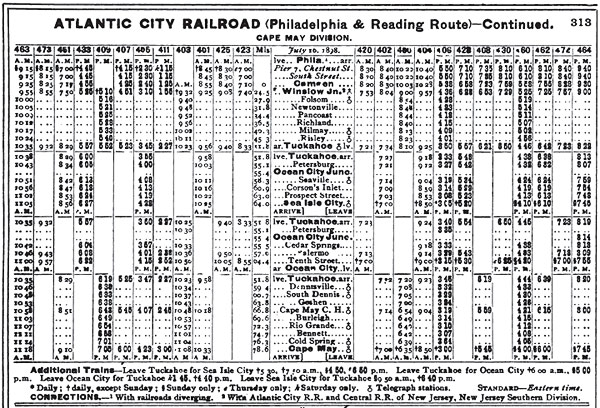

The results of the demonstrations were encouraging enough that on December 16 - after five years of claims of multiple patents - Holman applied for a bona fide patent, an Attachment for Locomotive Engines, although he was not entirely happy with its use of friction bearings on the axles. Athough the tests were brief, he could already see that friction bearings created unacceptable drag and were difficult to keep sufficiently lubricated at high speed, which could potentially cause overheating. |

||||||||||||

|

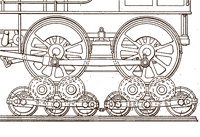

Bearings and rollers and wheels - On the right side of the image below is an early example of Hyatt "flexible" roller bearing of the 1890's. It used multiple short rollers layed end to end in a race, instead of only one long roller. It may have been the ideal bearing type fpr Holman, but instead he designed a hybrid of rollers mounted on sleeve bearings similar to the one shown below. His 1897 patent application, center, has fewer lead truck axles, but otherwise shows the arrangement of rollers mating with the axles in groups of two's and three's. The images at right show this arrangement on #1. (two photos: photographer unknown, Wx4 digital collection)

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

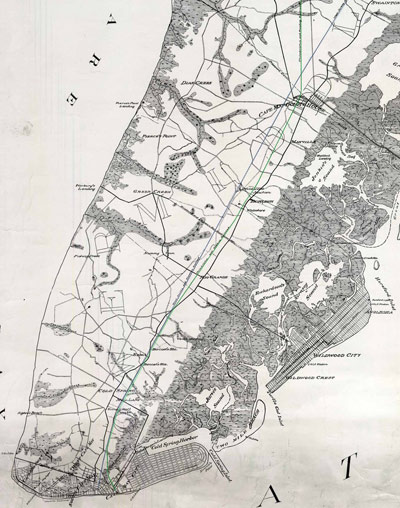

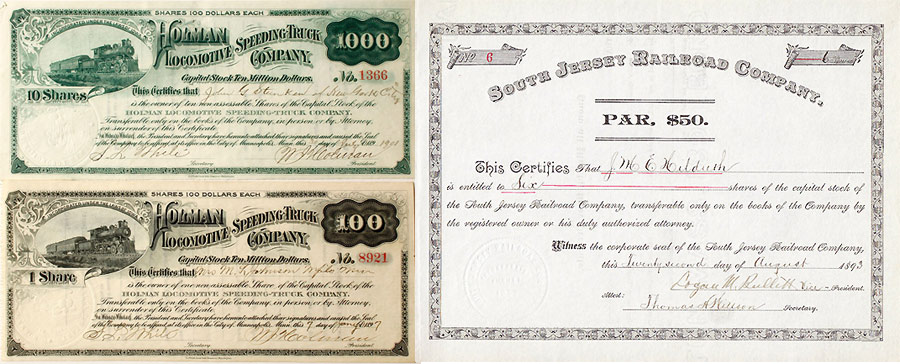

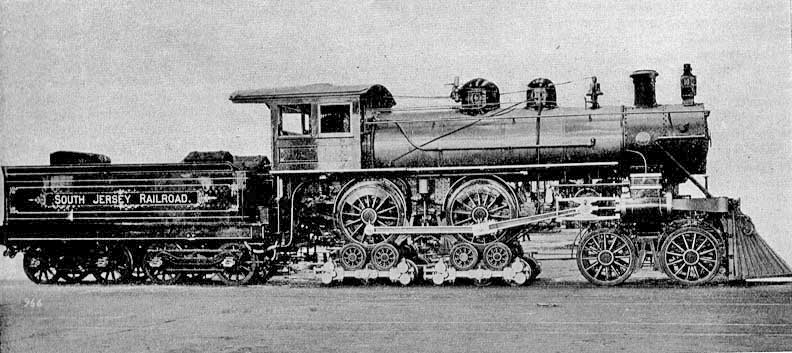

Following #1's August completion, cryptic reports surfaced suggesting that it performed some initial breaking-in at Baldwin's Philadelphia plant, after which the locomotive moved across the river to New Jersey to conduct a high speed trial on the Camden & Atlantic Railroad. Under ill-advised circumstances, #1 achieved 83 mph, prompting Camden's city fathers to ban Holman and his machine from town. Holman #1 then sat idle and homeless because Holman's reckless reputation with his screwball creation preceeded him wherever he went. Afer two months of inaction he stumbled across a colossal stroke of luck. He found a railroad that was more desperate than he was. South Jersey Railroad was not much, a Johnny-come-lately, half-hearted Philadelphia & Reading Railroad raid by proxy on rival Pennsylvania Railroad's Southern New Jersey summer seashore traffic. It completed its sand-ballasted line into Cape May in June 1894 and promptly went into receivership two months later, because its promoters had so thoroughly misread how empty the resort could be on either side of summer season. Southern New Jersey's once-abundant agricultural economy was then in decline, with farms being abandoned right-and-left, and another economic mainstay, the local glass industry, was withering from the effects of lower-priced foreign products. In low season, there simply was no traffic, passenger or freight. During the 1895 high season, the influx of resort traffic had outstripped its modest locomotive roster's capacity to handle it, but once the vacationers went home, the transformation was so dramatic that by October South Jersey receiver Francis I. Gowen cut manpower to one crew each for passenger and freight trains. Passenger service accordingly dropped to one round trip per day between Cape May and Camden. Yet... on November 12th, about two weeks after Gowen announced the cut in service, Holman #1 was reported as being placed on its trucks at Cape May. |

|||||||||||||

............ ............ |

|

||||||||||||

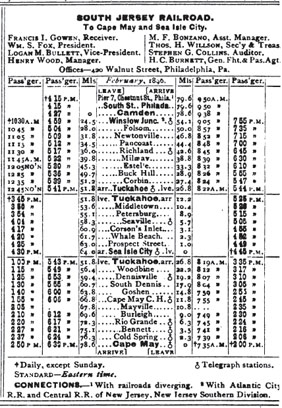

The crux of the matter: These two timetables starkly show the disparity between summer and winter traffic at Cape May. During the three month high vacation season, South Jersey had trouble keeping enough locomotives serviceable to cover the heavy traffic, but during the balance of the year, the usual two round trips per day ran largely empty. The schedule at left shows the situation in February, 1896 (in 1895 it was worse - one rounder), while the July, 1898 timetable shows the flood of trains that burnished Atlantic City Railroad's track in its first summer season after taking over South Jersey's operations. - both images from The Official Guide of the Railways |

|||||||||||||

No explanation of "why" it appeared accompanied #1's arrival. At that time of the year, all that Gowen could reasonably expect from the loco's presence was some free publicity and maybe a few fares from gawkers who might come down to the cape to witness a show. It was also an ace in the hole for the next summer, if it did not go to pieces in a wreck in the meantime. He may have considered the machine to be an ace in the hole to help him contend with the onslaught of traffic during the following summer. As events would later suggest, Holman's "stroke of luck" may have been purchased under the table with liberal amounts of stock. Both parties anticipated a prompt series of trials, but a short, nasty storm put things on temporary hold until November 18, when the right of way was pronounced shipshape enough to host a 54 mile dash up to Winslow Junction trailed by five coaches. As he would in the future, Holman arranged this event as a tightly controlled public relations stunt. New York Tribune later reported were 107 "railroad men, capitalists and reporters - the invited guests of W. J. Holman". He did not countenance known critics, who were excluded from his spectaculars as they were found out. If reports are to be trusted - a caveat that by now should impress the reader as being redundant - the locomotive made a good showing, covering the distance at a 70 mph average, with one short burst hitting 80. An overly-enthusiastic Holman predicted that a Winslow - Cape May run scheduled for the following day would cover the same ground in 30 minutes |

|||||||||||||

|

The second demonstration went poorly. Locomotive #1 developed a case of asthma, a "defective draught", that hobbled it so much that the inventor admitted the day's single speed spurt timed-in at three miles-per-hour less than the previous day's high (a less-biased account put it at below 60 mph). Holman's reputation with the industry as an amateur (at best) really showed at this point, for although his team failed to uncover the root of the problem, he none-the-less elected to put on another show at the end of the month. This one culminated prematurely after it was found that his engine could sputter along at no more than 25 mph. It was only then that somebody thought to crack open the smokebox door to find that the exhaust draught had been choked off by a pile of cinders that had collected inside a spark arrestor of new and defective design. A professional would easily have sniffed out the issue when it first occurred, but Holman kept none around. Quite perturbed and embarrassed, he loaded his locomotive onto flatcars bound for Baldwin "to have the cinder nuisance stopped". The Bee of Earlington, Kentucky scored the event, the inventor and the sum total of his endeavors with a nonpareil expression of insight:

|

|||||||||||||

|

At left is Holman's 1895 patent, which shows the main truck's second configuration, to which the original truck may or may not have been modified for placement under #1. A PDF download of all Holman patents is located HERE. | ||||||||||||

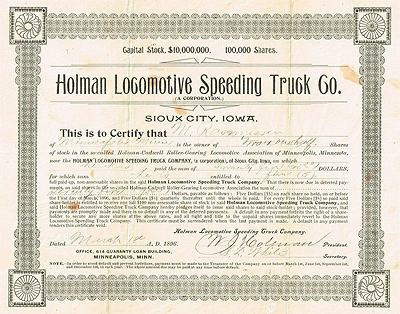

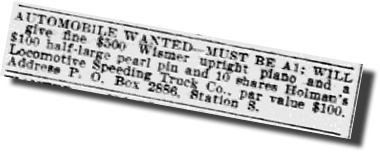

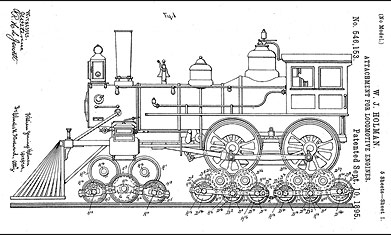

1896: Despite the setback, Holman judged the trials as promising enough to ramp-up his stock sales. In January, 1896 he, his namesake son and seven others, incorporated the Holman Speeding Truck Company. Oddly, their initial announcement declined to reveal the particulars of their proposed product, suggesting an attempt at secrecy, but our old acquaintance St. Paul Daily Globe chuckled that, "The device is not such a secret in this vicinity". Indeed, it was less than a mystery out in New Jersey, too. What surely took center stage attention, though, was company's staggering $10 million capitalization - the equivalent to more than $300 million in 2020 - an amount which left many people wondering why such an enormous amount of capital was required to fund the development and marketing of a mechanism that could have been farmed out to a medium size foundry. From its onset, the 'new' business's cover was blown as merely an upscale, more ambitious version of what Holman had been doing for more than five years. |

|||||||||||||

| Central to the new arrangement was that, as the patent holder, Holman assigned half of the stock to himself, which in his eyes made him an instant multi-millionaire. That must have been pleasing. He expanded the company reach beyond Minneapolis and Philadelphia by establishing sales offices in New York and and Sioux City (where the comany incorporated). His agents offered $100 shares for half that, and advanced a supposition to investors that they would easily double their money and more, once the trucks gained general acceptance by the railroads. Most assuredly, this was just around the corner, and sales went well. Engineering news reported in March that: Sales went well. Engineering news reported in March that:

In contrast to Holman's reinvigorated sales campaign, South Jersey railroad's financial difficulties had continued to intensify to such a degree that, by February, the bondholder's committee was seriously considering liquidation. In a lawsuit brought by powerhouse Pennsylvania Railroad, the court now had confirmed an earlier ruling that, as the second railroad to lay rails in the area, South Jersey would be required to replace its disputed at-grade crossings of PRR's West Jersey Railroad with overhead bridges, or otherwise yank them up and severely curtail operations. This time Philadelphia & Reading, which held the controlling interest in SJ, stepped in at the last minute with the required $19,000 funding out of fear that liquidation might result in sale to a foe, but not before South Jersey experienced a lengthy crime wave of vandalism and theft all along its line, perhaps instigated by PRR. |

|

||||||||||||

|

With the crossing issue resolved, South Jersey's board resumed plans to finish construction of a branch to Ocean City, even though its cost was expected to be about $33,000. P&R was not on board with that idea, so local residents banded together to charter their own Ocean City Railroad Company, which would be operated by South Jersey upon completion. The OCRR then let out a $33,000 construction contract to a ex State Senator Lemuel E. Miller, who subsequently tried to avoid paying his workers. In early May, after a month of this, 200 desperate and irate laborers, soon augmented by 100 Italian immigrants from another crew, seized two locomotives and set about to blockade the branch with ties, trees and large stumps. Tensions escalated further when a force of the contractor's hirelings attempted a rescue of the locomotives, but were repulsed by armed strikers. After week of semi warfare, the senator, who had remained scarce, finally relented, paid off the men, and sent them packing. On the same day, May 6, Pennsylvania Railroad consolidated West Jersey and five others railroads into West Jersey & Seashore Railroad Company, whose territorial domination would proceed to put SJ further into the hole. Then, just as drought-induced wildfires began to lay waste to Southern New Jersey's cranberry bogs and economy, the outfit which had supplied the Ocean City project with $26,000 worth of rail began crying foul and sued Senator Miller over non-payment. Miller had bid $33,000 for the OCRR contract, a severe underbid for which he and South Jersey paid later the price. As if all of this bad juju was not enough, towards the end of the month - concurrent with the onset of summer season - a violent thunderstorm demolished the Cape May depot car shed and the general superintendent suddenly resigned in a mysterious huff. By month's end, SJ and WJ&S were embroiled in a semi-formal speed competition, one that would continue on occasionally for decades. It was a natural-enough development for two competitors who ran within sight of each other for the eleven miles between Cape May and Cape May Courthouse, nearly half of it within 50 feet apart. As a consequence, South Jersey instituted a new fast train dubbed the Century Flyer by the winning entry in a naming contest. South Jersey officials must have figured that Holman's locomotive was an ace in the hole, but the inventor evidently was too busy signing stock certificates to be bothered with public exhibitions. It was close to two months before Holman got around to staging one. When the trials took place at last, they were an absolute Holman PR master-stoke. A wire service reporter wrote of the first run on July 29:

|

||||||||||||

In the assumption that the engineers of both railroads were nutty enough to pull out all the stops, this incident appeared as solid testimony that the Speeing Truck was capable of ripping along at high speed without piling up into a ditch. How much fuel it consumed during such a display of elan was another matter, well hidden from prying eyes. The reporter also alleged that, from scratch, the 11 1/2 mile run between Cape May and Cape May Courthouse consumed eleven minutes for an average speed of 60 2/3 mph. He also related that the speed indicator on the engine touched 90 mph once (another source claimed 94 11/12th mph), and spent much of the time hovering around the 70 mph mark. These figures, as almost always, came from Holman's contingent, for the reporter made no representation about riding the engine. The newsman was not completely wide-eyed, however and brought up some generally circulating skepticism surrounding Holman's claims of increased economy:

His readers were left to themselves to wonder how all of that extra machinery - twenty bearings supporting ten axles and twenty wheels - was supposed to increase efficiency. At this point Holman still may have been in denial that this was a significant problem, or if he did understand, he was not about to broach the subject. He clearly was more concerned about reaching speeds above the century mark than addressing concerns of fuel economy. Fuel economy was not the stuff of banner headlines. Indeed, if he actually did measure fuel and water consumption during the test - not a given - he would have insured that the figures never see the light of day. They would not have been encouraging.

|

|||||||||||||

|

South Jersey RR #10 or #12, Locomotive Engineering, 12-1898 |

|

||||||||||||

|

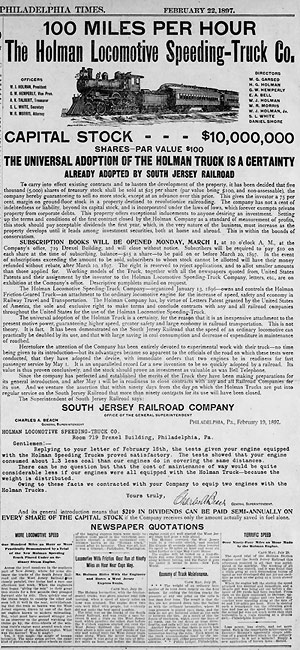

1897: "In a way, he has proceeded to out-Fontaine Fontaine." His 1897 campaign got to an early start. In February Holman began targeting large cities with a series of impressive quarter-page+ advertisements (see image at left) featuring woodblock likenesses of the locomotive and a bold print, all-caps proclamation that "THE UNIVERSAL ADOPTION OF THE HOLMAN TRUCK IS A CERTAINTY - ALREADY ADOPTED BY SOUTH JERSEY RAILROAD". Underneath, a reproduction copy of a letter from South Jersey General Superintendent Charles A. Beach (the replacement for the mysteriously departed super of the year before) proclaimed that because the Holman consumed about one-third less coal than his own locos while proving to be easier on the track, his railroad had ordered two of their own, scheduled for May 1st delivery, only three months away. The ad flatly asserted that, "The present adoption of the Holman Truck insures its universal adoption, and best of all for people who wanted to get in on the action, the company for a limited time would be offering the $100 par stock at a trifling $25 per share with an assurance that it would pay "acceptable" dividends the first year. Holman's device had finally cracked the big time, it seemed. |

|||||||||||||

|

(click above for larger image)

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

Fun question: Which stock certificate was worth the least? |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

In light of Holman's recent advances on all fronts, a reassessment of editorial policy towards him was clearly called for. Sinclair's journal reacted with dispatch:

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

To keep up with the anticipated clamor for orders, Holman proclaimed that two plants would be required, one to handle the East Coast trade and the other in Minneapolis to take care of the West (which presumably stopped at the foot of the Rockies' Front Range, where the restrictive inconveniences of tight tunnel clearances and stiff grades likely prove to be a damper on the market). In an interesting bit of timing, Holman announced the "probable" purchase of the abandoned Gilbert Car Works plant at Green Island, New York while his son and Sinclair were engaged in their editorial squabbling. The news may have been his personal response to the journalist - "You're now talking to a heavyweight, buddy!" - and it came with an assurance to stockholders that he had negotiated a splendid deal at half the appraised value. At the same time, he maintained that he was "under obligation to the city of Minneapolis" to locate a facility there (on fertile ground hosting his largest group of stockholders). The company's bylaws required that the directors be given 10 days advance notice of a large transaction to allow for deliberative meetings, he disclosed, so nothing definite could be announced for awhile. With the completion of the "South Jersey" engines still a ways off - Baldwin's schedule conformed to the requisites of reality, not an addled inventor's imagination - Holman had ample time to take full advantage to pursue sales generated by his waves of propaganda. As always, he assiduously avoided railroad men. In fact, he preferred to sidestep men altogether, because they were more apt to have some understanding of mechanical gadgets, a serious hindrance to sales. Besides, long experience told him that he did his best work catering to what he would have regarded as the frailties of women - appreciation of home, family, warmth, honesty and all that other nonsense. He was pretty good, not great, mind you, but pretty good at hiding his hard heart when need be. But by now he commanded a small flock of agents who each had his own method of parting funds from people. In May, Machinery revealed that they were "again" in Philadelphia, attempting to sell stock in their "prize freak in railroad lines". Holman was there, too. In between sales, he was in an opportune position to keep in-person tabs on the locomotives' progress at Baldwin. Perhaps he offered a few insightful suggestions regarding their proper manufacture. |

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

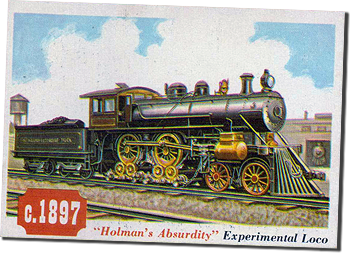

All dolled up in dark blue paint with silver lettering / trim and brass fiiting, South Jersey #10 poses for a Baldwin photographer in the only known extant builder's photo of a Holman Locomotive. The trucks on this loco were repurposed from Holman #1. The front truck may have also belonged to #1. Question: How did the fireman shovel coal from the subterranean tender into the altitudinous firebox? |

|||||||||||||

|

Going for Broke When South Jersey numbers 10 and 12 - painted a stately dark blue with silver lettering and brass ornamentation - belatedly made their triumphant entrance into Cape May on July 17th, the high season was already half gone. South Jersey men were VERY anxious to put them through their paces within the next few days. Concomitant to the locomotives' arrival, a local paper's society column announced that "Mr. and Mrs. W. J. Holman of Minneapolis, have arrived to spend the summer." Holman immediately injected himself and Kate into local society and began to enjoy the good life, mingling with hot prospects and the wives of high railroad officials who were too busy to take in the ocean air. First and foremost, it was all about selling stock - Holman's bunch had made that clear to Angus Sinclair years before. Joining them were sons William and Harry and their wives, daughter Nora and her husband, Speeding Truck Treasurer Thomas E. Eastwick, and daughter Birdie, accompanied by her husband and company secretary Strella Leroy White. One of the family's favored pastimes was participating in local card tournaments, where Kate and Harry's wife managed to win prizes. The extended crime family surely was at the pinnacle of their social existence. It would have been a wonderful summer for them had not something been amiss with the locomotives. Throughout the socializing, the locos remained backstage, missing both their their announced grand unveiling date, the subsequent rescheduling, despite repeated assurances throughout the balance of July that they would soon be unleashed. Then they vanished completely. |

|||||||||||||

|

So, what possibly could go wrong with a locomotice so awash with spinning gizmos? Whatever it was, the South Jersey boys' roundhouse skills proved to be unequal to the task of fixing, so Holman quitely slipped the locomotives back to Philadelphia to tax the patience of the Baldwin people.

On September 4th, the pair briefly surfaced to test the effectiveness of remedial efforts, and according to old friend St. Paul Globe, they hit 120 mph during a test run. No other newspaper carried the account, which raises more than a suspicion that Holman had invented the story to assuage stockholder rumblings at home. If anything really did take place on that day, it must have indicated that the trucks still needed more work, because the locos remained at Baldwin for another five weeks. South Jersey management's hopes of showcasing the novelties to summer crowds were dashed.

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

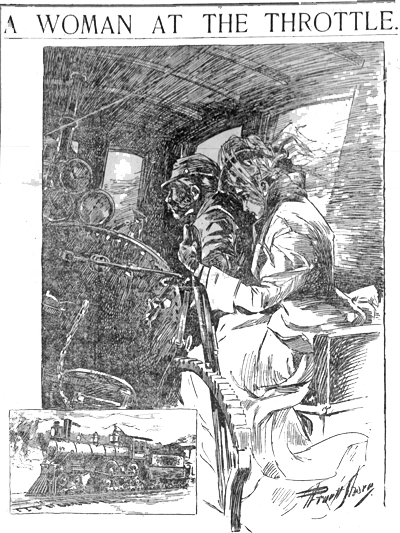

Late 1897: A Woman at the Throttle The same day, it appears, he and Superintendent Beach each received a telegram from a newspaper publisher requesting a two day series of charters. Nobody had ever petitioned for a charter before, but what undoubtedly caught his attention was the name of the sender, Joseph Pulitzer. Today we know Pulizer as "the father of jounalism, along with other attributes that the Pulitzer Prize Committee does not want to talk about. He was also a practioner (along with arch-rival William Randolph Hearst) of the type of high sensationalism and the yellow journalism that dumped the War of 1898 in America's lap. But that was still a few months in the future. In the meantime, he was always looking for some wild new exploit that one of his so-called "girl stunt reporters" could write up for a full page splash in the Sunday section of his New York City flagship newspaper, The World. He was intrigued by Holman's speed claims, but was also aware that they remained unsubstatiated. In the past, Holman was not about to proclaim an "official" attempt at the world's record supposedly established by the 999, since that might invite tight scrutiny from people outside of his control. Pulitzer's proposal was a cure for that. He proposed that the charters be exclusively attended by his ace stunt girl, Kate Swan*. She would give a straightforward report, not partake of the investigative journalism that appeared under her married name. Better yet, she would ride the locomotive.(see box at right) According to Swan, South Jersey's Superintendent Beach expressed some initial apprehension over another Holman outing:

Then, he gave his permission anyway. The thought of hosting the world's speed record was just too much for him to resist, unless his reluctance was contrived poppycock in the first place. If her timeline of events is accurate, Swan must have had her bags packed while Pulitzer awaited a reply, as the first special ran on the morning of October 20th, two days after Beach's OK.

|

..........above - Kate Swan at the throttle of Holman #12 - Buffalo Sunday Morning News, 11-28-1897

..........Preface, Table of Contents page - Depiction of Swan leaning out of cab at "110" mph that accompanied

|

||||||||||||

| "Then it began to run along" and by the time it approached the start, "The locomotive had settled down to a gait that made us feel like one long streak. There was hardly any wavering. None of the shaking and swaying that I had dreaded at first…The speed indicator gave us 110 miles per hour when we were upon the green flag. Stop watches clicked. McClain blew the whistle as we passed the flag.

And then the tension. Half a minute is not long as a lifetime goes, but, but McClain and myself, the fireman and Mr. Holman lived hours in time. I leaned far out of the cab window. Nothing but white spots could be seen of the speeding truck wheels. They were turning so fast the revolution could not be seen. All the shaking was gone. Watch in hand, I could sit bolt upright without support. There was nothing in the world but a long steel knife ahead that vanished the instant I realized it. Woods disappeared. Everything mingled and formed one brick red tunnel. The seconds were flying. Ah, would she make it. And then my heart stood still. It seemed as if No. 12 answered. How she did catch hold of the track and straighten out. No racehorse ever laid herself out, no arrow ever went straighter or stiffer to its finish. The red flag was not in sight, and from my watch I knew we would win. All I was conscious of [was?] the triumph. The speed indicator said 128 miles an hour. [Holman and Morrow claimed that they timed the last half mile in 27.5. seconds, 131 mph] Even as I read it I knew the red flag was passed. The whistle was blowing No. 12's victory out over all that Jersey loneliness. For another mile the victor flew along and then we slowed up. McClain and I looked at each other in sort of a dazed, speechless fashion, and nobody said a word… McClain picked up a bit of waste and and nervously rubbed the boiler before he asked how much. Thirty-two seconds was the time for the distance… McClain's first exclamation was: "Give me a decent track and I'll make two and a half miles a minute, I know." |

|

||||||||||||

| If Mcguirk's reporting was accurate, then this was a momentous event. But, she, like Pulitzer and Holman, had an agenda that mandated making a spectacle of besting the 999, and she was a central part of the show. The faster Holman's engine ran, the better it was for her. Essentially, her assignment was to produce a fluff piece for the Sunday section, not a serious investigative article slated for the front page. It plainly was not part of her mission to question whatever was spoon fed to her by a group of men whose record for truthfulness was rather dismal.

Given the lack of independent observers, it was a simple matter for Holman to doctor-up the outcome. The measured "mile", supposedly laid out by surveyors during South Jersey's construction, was a likely candidate for shortening - McGuirk was in no position to know the difference. At a time that virtually no locomotive had exceeded 100 mph - did a recorder designed for 128 mph even exist? McGuirk claim to have "leaned far out the cab window" at over 110 mph without negative repercussions is hard to swallow. (Note: I certainly was not foolish enough to stick my head far out the window at the comparatively glacial ~80 mph speed that I routinely operated my locomotives!) Suspicious as all of this was, none of it disproved the possibility that Holman #12 did achieve a remarkable speed. Mcguirk's description of her sensations at high speed match my own experiences, sensory overload that I think of as the "tunnel effect". "There was nothing in the world but a long steel knife ahead that vanished the instant I realized it. Woods disappeared. Everything mingled and formed one brick red tunnel." The one time that I sat in the cab of a locomotive traveling at the sort of speeds that McGuirk claimed, it seemed as if I was watching the event through a fisheye lens, much as she described. The track merged into an apparently motionless swath of steel ahead, while on the periphery, trees merged into narrow tunnels of green that expanded at the last moment to accommodate the train's dimensions. The experience was so foreign that my mind could not process it. To me, McGuirk clearly had traveled at a speed unprecedented for her, well above her 75 mph on the B&O. But how fast? There is no way of telling. People much smarter than me maintain that humans experience differential changes in perception of speed due to motion adaption, or as I would put it, after awhile your brain gets used to going fast, and adjusts. My brain was attuned to the jet age, not the horse-and-buggy era. One wonders, nevertheless. If the run indeed turned Engineer McClain speechless, as she claimed, it does suggest that he had entered into speed territory well beyond previous personal experience. What speed McClain actually achieved, we shall never know. Even theorizing a reasonable top speed for an engine of #12's power would likely wind up being an educated guess due to the significant numbers of unknown specs and variables. The most telling stat may have been that Kate Swan did not lose her hat. |

|||||||||||||

|

Holman's "world record" did not come as any surprize to Angus Sinclair, since he had heard it all before and now had Holman sized up as a bald-faced liar. What did amaze him was that late events had caused some of his fellow journalists to let down their guard. The Engineer, for example, placed a Baldwin builder's photo of South Jersey #10 front and center on the title page of its November first issue. Surrounding the photo was an article full of specifications and detailed explanations of the trucks workings & etc. that looked like it had been cooked up by Holman himself. Only as the article bled into page page two did the author, our past acquaintance W. Bartlett Le Van, - begin to express lingering doubts based upon what he witnessed during the October 14th test. He repeated his old assertion that the Holman's top speed was well under 100 mph, and attested about what we already know:

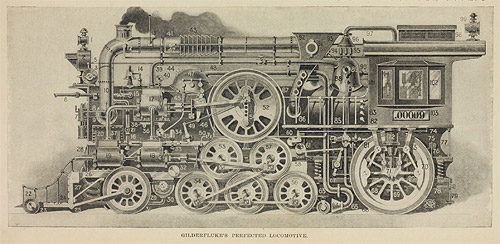

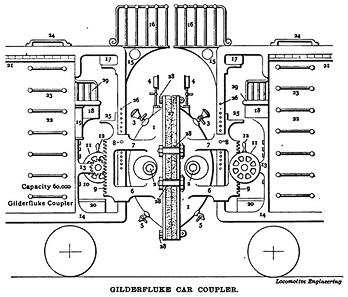

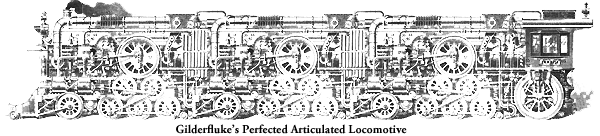

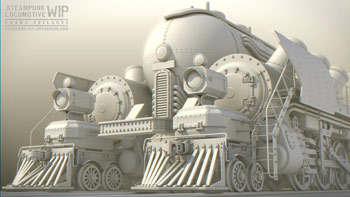

Levan made no mention of the locomotives' true ownership, which had to be irksom, to Sinclair, but overall the editor still seemed more amused than mad over Holman's recent successes. The illegitimate son Exactly who the inspired soul was that hatched Gilderfluke's Perfected Locomotive is a mystery. The original drawing of this convoluted hunk of mis-engineering may have started out as some bored Locomotive Engineering staff member's doodle, which later blossomed into the final 'perfected' product of chief illustrator, A. L. Donnel. It and its accompanying "brief description" formed a 3 1/2 page feature article that began on page three of the December issue. Its exquisite attention to implausible detail surely indicates that Gilderfluke was a grand collaboration of creative effort punctuated by uproarious laughter, the filling of spittoons and emptying of hip flasks. Angus Sinclair adopted Gilderfluke as his own. There also was little doubt that this brilliant foolishness was a potshot aimed directly across the Speeding Truck's cowcatcher to serve notice on Holman that the jig was up. Its patent genius was evident at first glance: the multitude of wheels was pure Holman, while the giant Freak-esque drive wheel unmistakably connected Holman to Fontain's fiasco, and that liberal application of external gimcrackery dealt a crushing knock upon the inventor's love of over-design. It was an absurdity met head-on by absurdity, and it was magnificent. If Sinclair's contingent found some smug satisfaction in their belief that they had finally exposed the stupidity of Holman's design, it was short-lived. As hilarious as it was, Gilderfluke was a highly esoteric inside joke that lost its meaning outside the tightly knit railroad fraternity. About all that it achieved was a reaffirmation of the industry's ongoing rejection of the machine as the work of an addled amateur outsider. Holman surely was offended, but again, his victims did not read the railroad trades. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

January and February, 1898 were fine months for Holman.* Newspaper editors continued to rehash the October stories of his locomotive's exploits, and he now held in hand a newly-approved patent for his redesigned truck. A fresh spring sales offensive was just around the corner, and to prime the pump, he let slip to St. Paul's The Appeal that his machines "may be in use in Chicago soon." While this never happened, in late February, South Jersey Railroad - forever short of motive power - announced that the locomotives would stay put to haul express trains during the coming summer. This was way better than nothing. Then, a few days later, creditors foreclosed upon South Jersey. Cape May business was simply too sporadic to carve up between two railroads. During its not-quite four years of existence, the company never came close to turning a profit. For a month, Holman's prospects remained in limbo as he waited for the foreclosure sale. This time around, Philadelphia & Reading was not about to stand back and allow Pennsylvania Railroad to swoop in. After placing the winning bid on March 29, P&R formed subsidiary Seacoast Railway Company to assume ownership, which it quickly leased out to another P&R subsidiary, Atlantic City Railroad. Atlantic City Railroad was no fan of Holman, having previously rebuffed his entreaties to run demonstrations. His locomotives were evicted along with South Jersey's corrupt management. |

|

||||||||||||

|

Whac-A-Mole and a curtain call after the show shut down Suddenly the one railroad company on the continent that was willing to host his Speeding Trucks was gone, never mind that after three years of trying, his plan for elevating his locomotives from the sand lots of South Jersey into big league railroading was crushed. In the past, he remained resilient in these down moments, but now, at close to 80, he lacked the energy to pull himself through. By summer he went missing, dividing his time between Minneapolis, Philadelphia and perhaps elsewhere, to avoid pursuing stockholders in a game of Whac-A-Mole. Financial journals pronounced his securities as worthless. Locomotive Engineering labeled this "The End of the Holman Monstrosity", but the pundits were premature. With the revenue stream dried up, finances soon became so tight for the Holman family that daughter Birdie, son-in-law Strella (who had returned to selling real estate) and their three young children moved in to her parents' home, already shared with her sister Nora and brother Oliver. With the two company principles responsible for signing stock certificates literally in-house, it was probably inevitable that, once the heat was off, they would return to their old game, which they did for a short time in 1901 with little success. Without the demonstrations, it was tough to drum up enthusiasm. This all must have been too much for Strella, for he soon abandoned his family, causing Birdie to divorce him in 1902. |

Google Maps Street View of former W.J. Holman house today |

||||||||||||

|

Shortly after receiving word of his ejection from South Jersey, Holman sold loco #1 to Buffalo & Susquehanna, but the exact fate of #10 and #12 and their trucks is unclear. Baldwin received a "special order" for something pertaining to them in June, 1898, which probably means that they were being readied for sale as conventional locomotives. He hung onto his original friction bearing truck (a reporter later mentioned that it had bronze sleeve bearings), however, which he brought out of mothballs in February, 1904 more than six years after the Pulitzer special. Somehow or another, he had managed to cajole a genuine big time railroad, Buffalo, Rochester & Pittsburg (later part of Baltimore & Ohio) into a trial run. Rather than being a publicity stunt as in the past, this one was a genuine demonstration run ostensibly put on to entice BR&P officials into a sale. Even the railroad's president had enough curiosity to show up, although it is hard to fathom his railroad's interest given its generally hill and dale profile that required mammoth, small-driver locomotives to cope with the grades. For the most part, BR&P was no racetrack. By February's end, BR&P people had placed an unknown locomotive on top of Holman's Speeding Trucks in its DuBois, Pennsylvania shop. BR&P had no locos so small in stature that they would mate with his machine, so it is possible, even likely, that nearby Buffalo & Susquehanna allowed the former #1 to be re-united with its trucks. The tests then awaited Holman's arrival from New York City, which had been delayed because of a "slight indisposition" of his health. When he finally was fit enough to travel, he chose to go home to Minneapolis, where he died on April 9th, less than two months short of his 85th birthday. Three weeks later, the Patent Office granted him a patent for his latest compound rail permutation. W.J.'s son Harry, who had performed all of the heavy lifting in the event, carried on. The Holman Locomotive made its farewell runs on May 24, 1904 on the 12 mile expanse between Rochester, New York and outlying Scottsville. Young Holman had no opportunity to doctor the results this time. The loco managed a 70 mph average over the distance, but but it lost 40 pounds of steam in the process due to a ride so unsteady that the fireman could not heave coal into its firebox. (Were all the previous claims of a smooth ride contrived, or was BR&P track that bad?) Afterwards, the crowd piled off to watch the Holman perform a one mile speed burst, which the BR&P men timed at 44 seconds (82 mph). As respectable as the performance was, the BR&P superintendent-in-charge was underwhelmed enough to score it as "satisfactory", a kiss of death that Harry totally misconstrued. He proclaimed there would be more tests in the future, but they never came. In the few years since the Cape May trials, steam locomotive technology had raced by while The Holman sat motionless in a siding.* In early 1905, Sinclair's journal, ever ready to lambast Holman's foibles, reported the engine as resting "at liberty". The demonstration was brief, but conclusive. Given an "honest" chance, the Speeding Trucks's performance did not match the hype. The miracles of friction gearing only exhibited themselves within the doctored universe of Holman, and Holman was dead. His death went unremarked outside of the Twin Cities area, and his family surely supplied the inauthentic biographic data used to note his passing. Fittingly, only old ally St. Paul Globe covered his death as news, with a two paragraph article that name-dropped his famous cousin William S. Holman in the headline, a good indication about which of W.J.'s lifetime accomplishments was deemed the most significant. The Globe also related that "though not widely known in the city he was well known in mechanical and scientific circles," yet not even Angus Sinclair recognized his passing. The Improvement Bulletin of Minneapolis, which dealt mostly with construction and architecture, was the only professional journal to run an obituary. It read:

|

|||||||||||||

|

Minneapolis Journal ran the only other obit, a more perfunctory one that included photo of him as "Edward J. Holman" (at left). Whether this was a mistake , or a victim's mild attempt at getting even, we do not know. For what anybody besides his victims cared, he might as well have been Edward J. Holman. He exited life as a forgotten man, except to his equally overlooked victims, a fitting tribute to a largely wasted life. His family held the funeral at his duplex home in downtown Minneapolis, the de-facto Speeding Truck headquarters for the last decade and one-half. Its exceedingly modest dimensions presumably were sufficiently roomy to handle the mourners before they removed themselves to Lakewood Cemetery for the interment. Philadelphia Inquirer 5-13-1905

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

Holman's lifelong progression of scams ultimately all went south on him, this we know, but that does not necessarily mean he deserves a summary judgement as a total failure. He did achieve a measure of success in that he never spent time in prison and managed to live comfortably (but not sumptuously) off of the proceeds of his defeats. This ranks him as a fairly adept confidence man, better than the jail birds, but a bush leaguer compared the big-timers who milked not only stock holders, but entire markets. |

|||||||||||||

| One has to suspicion that at some point - perhaps when he realized that his 1897 trucks created more drag than the originals - Holman may have come around to the idea that friction-gearing was a mistaken concept, but that was the beauty of being a con artist. The scam would continue as long as he could maintain the illusion of valid science well enough to keep the subscriptions rolling in. After all, to his cold heart, everything ultimately was about the money. We still do not know if he kicked small dogs, however. |

|||||||||||||

---

---