|

Taking Stock of William Jennings Holman and His Improbable Locomotive, Part 4

|

Preface / Table of Contents

Part 5: Moonshine Narrow Gauge: |

|||||||

|

a first strike at South Park and a strike out with buffalo |

||||||||

|

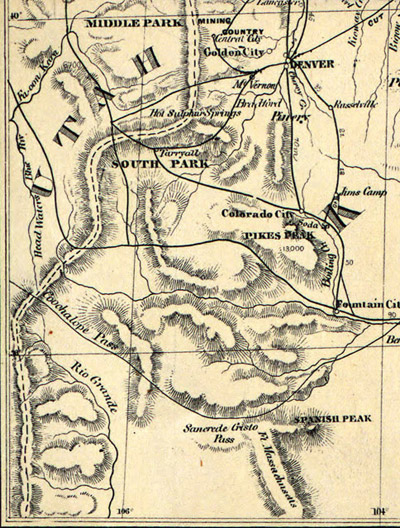

Let us tarry - all. Holman evidently gleaned enough cash from FW&S to carry him and his family through the four years following his inelegant departure. No record of gainful employment has surfaced, but he did dabble in Republican politics. In mid 1858 during a local party convention, he offered himself as Hamilton County's candidate for U.S. Congress, but was thoroughly whipped by the other candidate, 125 to 26. Fort Wayne & Southern was still too fresh in people's memories. His loss was good timing, for if he had gone to Congress, he would have missed out on an opportunity that opened up out wast that summer, one that had a natural appeal to a get-rich-quick kind of guy. A couple of Georgia prospectors had struck gold at the Gregory Diggings, which was located where the town of Central City immediately arose up the Clear Creek Canyon west of future Denver. The Pike's Peak gold rush was on.(see Side Note) At the end of the year, a group of now rich Georgia ex-prospectors visited Louisville to tell stories which may have provided the spark that ignited Holman to join the hunt. Holman could not simply jump on a horse and head west, because he had a family, his second wife Martha (Butler, b. 1834), daughter Ada (b. 1853), and two others, possibly including boys named Charles (b. 1855?) and Edwin (b. 1857?). He had married Martha in 1852, the year following the death of his first wife Rebecca (Burk, b. u/k), with whom he was apparently childless. Dreadful stories of the conditions in the California Gold Rush mines had circulated widely over the last decade, causing wise men to leave their families behind while they risked themselves in their typically fruitless quests for riches. Holman was not a wise man - never was; never would be. Hence in the spring of 1859, after the hazards of winter had passed, he and his young family joined a party of Hoosiers for the lengthy journey to Pike's Peak country, presumably first by riverboat to Kansas City, then by wagon over endless prairies still teeming with bison. Holman may have been seeking something else in addition to gold - a new life relieved of lawsuits and social rejection arising out of his FW&S mischief. He must have been smarting over his election thumping, as well. By the time his party arrived in June, the diggings were well picked over, so Holman and seven men decided to prospect in less crowded territory. The group included two men from Noblesville who had accompanied him across the Plains, A.J. Allison and James A. Gray, and they soon picked up six more men from Wisconsin. It was blind luck that guided them southwest toward the great South Park, until then only known to Indians and mountain men, and today by its scanty few residents, along with fans of the TV show of the same name. After about two weeks of alternately tramping and prospecting, they wandered across promising deposits of placer gold along a little creek. When one of them suggested that they investigate further, Holman agreed, proclaiming, "Let us tarry -all." thereby unintentionally giving the site of the future, but short-lived town of Tarryall its name. He and his cronies settled in to so some serious mining, and once news got out, new arrivers found that Holman's crew had staked out most of the promising placers with oversize claims, which they refused to share according to custom and law. This prompted the latecomers to cry foul, relabel the place as "Graball", and depart to search for a more promising spot. They soon found one a few miles away, and in a fit of spite, they named it Fairplay. Allison and Gray apparently claimed the richest spot, soon finding enough gold to quit Tarryall in favor of the politics involved in setting up the Provisional Territory of Jefferson. Allison easily won election as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, while Gray won a seat in the lower house of the legislature. This must have riled the boys over at Fairplay. Jefferson was a locally born, extralegal arrangement that squatted on parts of six existing U.S. territories, causing it to remain unrecognized by the Federal Government during its eighteen months of existence before the Territory of Colorado came into being. How Holman fared as a prospector is uncertain, but he seemed to have found moderate success, enough to divert his concerns away from his family. A wise man would have sent his family home after repeatedly witnessing communicable diseases of every variety rampaging through the filthy mining camps, but Holman failed to do so. Sometime during 1860, likely summer, his decision played out when an unknown sickness (cholera, typhus, typhoid fever?) took Martha and their two younger children. The tragedy left Holman in a bit of a pickle about how to care for Ada. The same summer, a young woman named Katherine White arrived in Denver along with a sister and two brothers in a company of 25 wagons from Indiana. Kate, as she preferred to be called, was 26 years old and had attended Oberlin College for at least two years, quite possibly graduating. She and her party hailed from Westfield, a small town near Noblesville, which raises the probability they were acquainted with Holman beforehand and a reunion followed their arrival. Kate and W.J. struck up a relationship in short order. When her siblings decided to return home in May, 1861, Kate said in a letter to one of her sisters that she would not accompany them. Instead, she was headed for Tarryall, and on August 4th, she became a Holman. They concluded that grubbing for a living was no way to move forward, so Holman sent Kate back to Indiana, where she arrived in late October. By then the women in their families could see signs that she was with child, but she could not produce the marriage certificate that would have made her condition respectable. A fair measure of familial discomfort followed until her husband arrived several weeks later holding the requisite document.Their daughter Martha arrived three days short of nine months after their marriage. Another daughter, Althea, and their first son, Harry came along late in the decade. He and Kate lived together until the end. Fairplay went on to become the county seat of Park County (a position it still holds) and also a station stop on the Denver, South Park and Pacific Railroad. Tarryall became a ghost town before the end of the Civil War. |

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

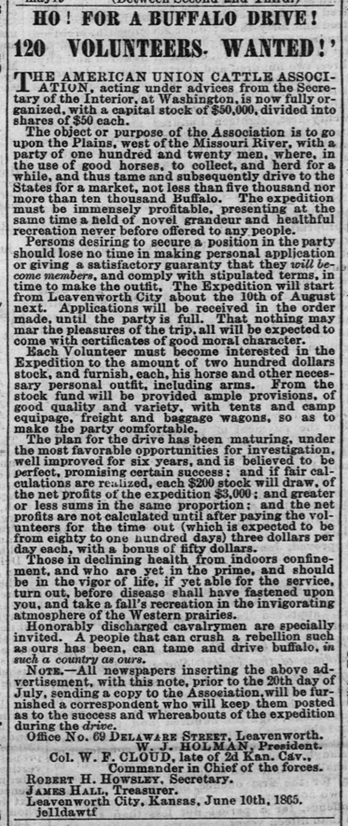

"You can't roller skate in a buffalo herd."* * With apologies to Roger Miller On June 17, 1865, at about the moment when the last sourdough called it quits with Tarryall, a very peculiar advertisement appeared in the Leavenworth [Kansas] Times. The advertiser was the American Union Cattle Association, and while the organization's name sounded conventional enough, its proposal was quite novel: The object or purpose of the Association is to go upon the Plains, west of the Missouri river, with a party of one hundred and twenty men, where, in the use of good horses, to collect, and herd for awhile, and thus tame and subsequently drive to the States for a market, not less than five thousand nor more than ten thousand Buffalo. The expedition must be immensely profitable, presenting at the same time a field of novel grandeur and healthful recreation never offered to any people [author's note: excepting maybe all of the Indians, some of whom were stuck in Kansas partly on Joseph Holman's account]. Five days later, the same journal published a letter from the association president which further laid out the plan's most minute details in a column-plus of painful prolixity . A tiny sample: Starting from Leavenworth City about the 10th of August,… we go into the country where the buffalo are; which is well known to be an open country without timber enough enough anywhere appearing, for hundreds of miles in extent, in which a single buffalo could conceal himself; and there, on the line of some small watercourse, in the midst of the buffalo, locate seventy-five horsemen. Awkward phrasing aside, would the country be open if it was timbered? Further down, he further sorts out his thoughts on trees. We have no historical accounts of any well laid designs, or intelligent and happily executed plans, to tame and drive the buffalo. An attempt, at anything like this, in the early settlement of the country, when the population was confined to the Atlantic Coast, would have been impracticable, owing to the immense forests of that portion of the continent. Yep, this leaves little doubt that this indeed was our boy's work, and the advertisement made it clear that the association's formation was no spur-of-the-moment undertaking. Said Holman: "The plan for the drive has been maturing, under the most favorable opportunities for investigation, well improved for six years, and is believed to be perfect, promising certain success…" During his travels back and forth through Kansas, Holman had encountered enormous herds of American Bison, and the way his mind worked, there had to be some way to take advantage of all this free meat on the hoof. When exactly he concluded that buffalo could be herded to slaughter is unknown, but whenever that was, he was not taking second opinions. Central to the association's activities was capitalizing itself with $50,000 in stock, available at $50 a pop. In this regard, the cowboys were not going to get off with a free ride, because along with providing their own kit and horses, "well tested for spoed [Dutch for "haste"?] and bottom", the herders were required to make a $200 stock buy-in just for the privilege of chasing crazy-spooked buffalo all over God's creation. |

|||||||

|

His plan was not well received. Some people believed that he had a darker motive hinted-to by the association's name. "Cattle" looks to have been a dog whistle to attract funding from cattlemen who were salivating over the prime grazing land that inconveniently was occupied by its rightful owners, including the surviving Potawatomies. What better way to get rid of the Indians than by driving off their food supply and starving them out? If Holman shared father's sentiments, he would have had no compunctions about what we would regard as genocide today. True aim or not, its mere suggestion immediately catalyzed a nation-wide wave of condemnation, a surprising reaction given the general state of antipathy between whites and Native Americans at the time. The prevailing assessment of Holman's plans had nothing to do with social issues, however. Jayhawkers viewed the suggestion that the idea of controlling beasts that were notorious for their flighty, contrary nature was downright idiotic. Said the Editor of the Prairie Farmer: We haven't anything to say about the absurdity of the scheme but merely wish to record it as among the things that could have originated nowhere but with the "universal Yankee nation." If successful, and perhaps this is not necessary, we shall next expect to hear of an expedition to drive down all the white bears from the polar regions and of a consequent famine among the Esquimaux." As a counter, the man that Holman had chosen to conduct field operations, "Commander in Chief of the forces" Colonel W. F. Cloud, late of the 2nd Kansas Cavalry, described himself as a veteran "rough and tumble" sort who was fully capable of the task at hand. Colonel Cloud's avowal of expertise had minimal effect on the fun-poking. One irreverent Norfolk, Virginia editor wondered if the association anticipated catching bison by the horns or tail, but a self-described Arkansas frontiersman summed it up the best:

Holman gave up and went home to Indiana after two months with his buffalo tale between his legs. His largest miscalculation, the one that fundamentally did him in, did not arise out of his ignorance of bison, but instead came from his misunderstanding of the universal financial state of young cowpokes: broke.

As far as we know, the aborted buffalo stampede was Holman's second-to-the-last adventure out west. Five years later, he and a fellow named Samuel F. Swayne shared a contract let by the U.S. Surveyor General to lay out a northward extension of California's Mt. Diablo Meridian. To gain the contract, he may have used his connection with his cousin, Senator William S. Holman.* After an audit, The Interior Department reimbursed the two men for a great deal less than the contracted amount, presumably because they had not fully fulfilled its terms. In his old age, Holman claimed to have laid out the entire meridian, rather than admit to a mere tag-on survey done years later. |

Part 5: Moonshine Narrow Gauge:

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|||||||