|

Taking Stock of William Jennings Holman and His Improbable Locomotive, Part 5

|

||||||||||

|

a cure worse than "the Fever" |

||||||||||

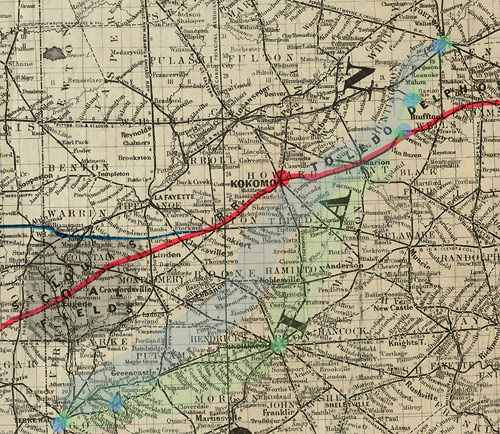

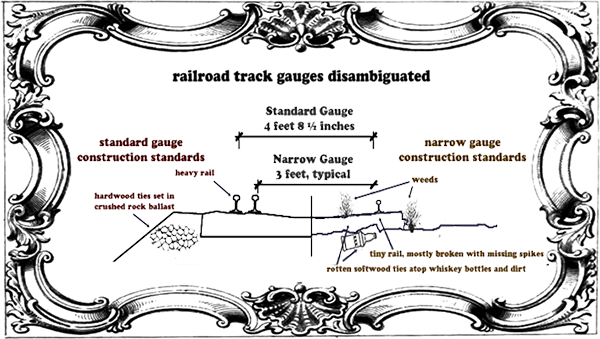

Between the early 1870's and the mid-1880's, America engaged in what has since been labeled The Grand Narrow Gauge Experiment, but people of the time characterized it as "narrow gauge fever". Narrow gauge railroads - so-called because their rails typically were placed three feet apart, rather than 4' 8-1/2" 'standard gauge" - found their highest and best use highest and best use the Colorado Rockies, where Denver & Rio Grande first managed to thread slim gauge rails through tight clearances and corners that no standard gauge line dared to tread. The Rio Grande caused a sensation in engineering circles, but what really excited entrepreneurs was how inexpensive it could be to get a narrow gauge railroad up and running. (PLEASE CONSULT THE FOLLOWING HELPFUL GRAPHIC SHOULD YOU STILL BE UNSURE ABOUT WHAT CONSTITUTES "NARROW GAUGE") |

||||||||||

_____ _____ |

||||||||||

|

The above disambiguation of track gauges comes with caveats. Standard gauge was sometimes referrred to as "broad" gauge, particularly in towns where narrow gauge railroads arrived first. But the generally accepted definition of "broad gauge" is anything wider than narrow gauge, although five foot broad gauge was the standard gauge of the South until 1886, when they narrowed rails to 4' 9", which meant that Southerners still considered *real* standard gauge as narrow gauge until they subsequently gave in and narrowed their tracks to standard gauge. If one includes other countries in this discussion, it becomes hopeless.

Somehow, cheap to construct came to be misinterpreted into cheap to operate, a woeful mistake. Once that chasm of logical disconnect was spanned, the narrow gauge contagion spread to the Midwest like wildfire, where overworked printing presses churned out scores of paper railroads in no time. St. Louis, which hosted a series of National Narrow Gauge Conventions between 1872 and 1878, became the lilliputians' capitol, but arguably Indiana was infected the worst. The state legislature had failed to pass any meaningful railroad regulation for decades, so it was wide open country for paper hangers like Holman. At the height of the narrow gauge madness, a perceptive, but anonymous Indiana critic addressed the overall situation with a brilliant summation of the railroad finance game: Railroads are built on three gauges; broad [standard] gauge, narrow gauge and mortgage. In other words, an awful lot of narrow gauge outfits formed with no intention of building a railroad. Their sole aim was to squeeze whatever cash they could out of company assets to line their own pockets. Investors faced the daunting challenge of separating the wheat from the chaff, given that all species of railroads engaged in the same general set of fund raising activities. Actual "construction" was not necessarily an indication of honorable intent, either. Sharpies like Holman, as he demonstrated with Fort Wayne & Southern, camouflaged inactivity with promises of work being just "two weeks" off, or when pushed into it, would contract with a local yahoo to shovel a little dirt around. With all this said, it is a wonder why Holman did not join Indiana's narrow gauge laissez-faire paper chase until 1878, when it had already run half its course. After his Mt. Diablo survey, he dropped out of historical sight for nearly a decade, which raises a pressing question about what was he doing that was so important. He continued living in Fort Wayne with his family, as far as we know. Kate gave birth to two more children during this period, Viola, who died in infancy, and William Jr, but that is as far as the intelligence takes us. Speculatively, he might have spent these years leading survey parties, as he claimed to have surveyed more than a thousand miles of railroad during his life. Or, he may have been involved in some stock scheme or another that has thus far escaped us. Maybe he did jail time. Take your pick. Of the paltry few railroad laws that Indiana did have on the books was one that allowed an individual to incorporate himself (women needed not apply) as a railroad, sort of an inverse precursor to the U.S. Supreme Court decision of a few years back mandating that corporations be afforded many of the same individual rights as actual people under the law. On February 2, 1878, William J. Holman sauntered down to the courthouse in Markle, 10 miles southwest of Fort Wayne, to file papers making him a corporation with the alias Fort Wayne Markle & Southwestern. Markle, Indiana then had a population of ~220, and was so backward that it would not get its first saloon for another two years. So, why Markle? One theory might be that Holman had spotted some fat and loose money belts during a couple of town rallies attempting to drum up civic support for a railroad connection to the outside world. When he incorporated "the Markle" (the name immediately assigned to it by newspapers), he boasted that he had already had obtained $25,000 in subscriptions, so there may have been something to this. But he soon learned that he had committed a significant legal error, for Indiana law, as puny as it was, specified $50,000 as a minimal requirement for incorporation. The error was easily fixed. He simply doubled his claimed amount. This leads to a more supportable theory that at incorporation, the Markle was funded by whatever change was jingling around in Holman's pocket. The Markle's capitalization amount - a very reasonable $990K, considering he proposed to somehow span the 175 mile territory from Fort Wayne to Terre Haute - was one of the few things about its totality that was set in stone. His literature did disclose that, beyond the cities represented in the name, his narrow gauge intended to call upon Indianapolis, a city already bulging at the seams with standard gauge lines. Beyond that, his plans got a little hazy. His corporate filing merely provided a list of counties through which the tracks would pass, but with a proviso, "or such of them as may be the most convenient". If this was not vague enough, he added, "The probabilities are that the company will avail itself of the roads already built in the general direction of the proposed road." All righty then! All investors had to do was anticipate how Holman was going to connect the dots. He was not really sure how he was going to do it himself, but that was the point, really. By keeping the route unsettled, he could troll the entire region with a wide net, rather than cast a few barbed hooks. This broad stroke enabled him to set communities, and even individuals, into competition with each other over right-of-way, shops and depot locations. The game was as old as railroading itself, even though in the case of narrow gauge, it occurred in a slightly different context. By now, competition among railways had evolved into a clash of titans over control of massive territories. The conflict in Indiana was particularly intense due to its strategic location between west and east, and one might conjecture, because the geography was so embracing to railroad building, that overcoming the earth's curvature seemingly presented the major challenge. Railroads necessarily kept their agricultural shipping rates high to finance the ongoing maneuvering, so when the narrow gauge concept of cheap transportation appeared, the Midwest was quick to adopt it as a cut-rate David to the standard-size Goliath. As such, narrow gauge fever was one of the country's first massive, if wholly disorganized, grass roots attempts at countering the railroads' monopolistic abuses of the American farmer. The Granger Laws passed by the Midwestern States, notably excluding Indiana, are better known, because their successes in curbing excessive railroad rates directly led to the adoption of the Interstate Commerce Act, but narrow gauge fever's contribution to the Granger Movement was significant. For a guy with modest talents, but limitless chutzpah, narrow gauge was a dream come true. The egalitarian qualities of the movement aligned perfectly with Holman's favorite sales approach of appealing to anti-monopoly sentiment and civic pride with a sincere one-on-one approach. Lamentably for him,this simply was not enough to penetrate the fog surrounding the Markle. Nobody wanted stock in a company that was not quite sure where it was headed. To pick up the slack, he turned to his other favored cash source, the public subsidy. In April, he and Markle treasurer Dr. David R. Buffington initiated a campaign on Fort Wayne for handouts under the guise of further defining the railroad's location in the city. This, they hoped, would encourage industrial wards into healthy competitions over depot, shop and yard sites that would generate the awarding of hefty honorariums to the company in exchange for these plums. Concurrently, they also hit-up the city as a whole for some easy money. Holman surely was dreaming of Jeffersonville, but this was bargain basement railroading that he was selling, so he was forced set his sights accordingly low with a plea for only $65,000, which he said would be sufficient to get the company in running order to handle the fall wheat harvest. That the company's actual route was still up in the air evidently was not wholly off-putting, because the town council very reluctantly consented to setting up a special election for June. To help prime a favorable vote, Holman put out reports in May that surveyors were in the field, somewhere. It almost worked. The subsidy lost by only a hundred votes. Such a near miss encouraged him to try again. Two weeks later he began drumming up support for a second try. The town council would have none of that. Holman and his cohorts continued pushing the idea throughout the summer, but managed to make a muck of the Markle's chances in the process. The surveyors and their survey evaporated, and Holman gave no hints about construction and continued to be coy about the future residence of his shops. The lack of substantive activity beyond solicitations for funds traditionally was a red flag, as we have noted, but Holman persisted - lack of persistence was not on his laundry list of faults - and by summer's end he had managed to hound the town council into conducting another vote. Holman's equivocation regarding the shops was a hot topic, and he somehow got cornered into making a monstrous error - he admitted that he now was considering nearby locations outside Fort Wayne, as well. This suggests that he already had a hot prospect lined up, but had hoped to make the revelation after the election. This sorely vexed the good citizens of Fort Wayne, and things did not go well after that. Although a petition to the county commissioners failed to stop the election, local newspapers insured its outcome by prominently displaying an in-common boilerplate "vote no" ad in their pages for several days prior to the event. On the big day of October 15, the Markle lost big, by 1200 votes out of 3365 votes cast. The overwhelming loss revealed that Fort Wayne voters had plenty of time between elections to compare notes on Holman, and the more they compared, the worse he looked. Jeffersonville's debacle surely came up, as did questions about Holman's character. Railroad Gazette commented that the results "probably killed" the Markle, which they would have had the Markle been on the level. Holman, it meant that there was one less cow to milk, but he had not yet gone through the entire herd. A week later he paid a "pleasant call" on the editor of the Indiana Herald, who reported this of the "the master-spirit" of the Markle: "He is sanguine of the eventual success of his enterprise, and that he is right, only ahead of the times." In point of fact, he was well behind the times, and his moves during December, 1878 showed his awareness of that. During the election, it was becoming apparent that two nearby railroads might actually lay tracks in the near future. One was a narrow gauge company that aimed to build from Toledo to Indianapolis (later revised to St. Louis), representing a direct fund-raising threat that intended to parallel much of the Markle's still nebulous route to Indy. The other was was a company of infinitely grander design, the Chicago & Atlantic Narrow Gauge Railroad, headquartered in Huntington (due west of Fort Wayne) that since 1873 had been plotting on paper in a very Holmanesque manner to connect the Windy City with an undetermined point in the East, most likely somewhere in Ohio, or maybe New York City, or Pennsylvania. It all sounded like so much baloney, but by December C&A had amassed a supply of ties in Huntington sufficient to begin construction of its trans-American narrow gauge main line… all the way to Markle, 10 miles to the southeast. (see box at lower left) |

|

||||||||

|

Just before Christmas, Holman approached the town of Warren with a revised plan. Warren, 10 miles south of Markle, was situated on the survey route for the Toledo-Indy narrow gauge, which already was running to nearby Bluffton. For a paltry $25,000 awarded to him in 10% / month installments, he would link their town with the a-building C&A at Markle. The Warren News curtly reported of this, "The [town investigative] committee reported adversely to the proposition on account of the insecurity given that the road would be built." No further news about this railroad appeared for six months. When it did, it was framed as an effort "to revive public interest in the Markle Narrow Gauge". Evidently, Holman had suspended his activities following the gut punch from Warren voters. A similar report of reawakening surfaced in the fall, and finally, in December, 1879 he located some high-hanging fruit at Lancaster Township, which agreed to hold a special election over support. Lancaster Township sat between Markle and Warren and was a thoroughly rural part of Huntington County that contained only one small hamlet. It was the bottom of the fundraising barrel, a good indication about how poorly the revival was going. The announcement came just as C&A was finally laying its final few rails into Markle. It's anticipated opening had initially been delayed from the previous December by lengthy and severe snows, which were followed by more-prolonged inclement conditions inside the company vault. Again, the Markle lost in a landslide, 78% against. In February, 1880, the board of directors held its last meeting a few days after a hoard of "anti-narrow-gauge" crusaders met in Huntington, presumably equipped with torches and pitchforks. Recall though, that Indiana was awash with the likes of the Markel, so Holman may not necessarily have been the main point of order. Whatever the case, the Markle had breathed its last, although its un-dead corpse would wander about the Indiana court system for years ahead. A year after railroad's demise, in the course of an editorial advocating tighter regulation of railroad start-ups, the editor of the Indiana Telegraph penned a fitting epitaph:

|

|||||||||

|

As an accurate description of Holman's narrow gauge, this rather tasty nugget of journalism was spot-on, but as an epitaph, it was premature. This is where the story becomes a tad strange. On March 27, less than five weeks after the Markel's board's final meeting, Holman incorporated himself again, as the Fort Wayne, Warren and Brazil. Holman now was a narrow gauge precursor of Wrigley's Doublemint Gum: two railroads in one! As an external entity, the Brazil (as we shall dub it) road was a near doppleganger of the Markel. The only apparent difference between the two was that the latter was projected to run north of, rather than through, Indy. Markle was still onboard despite being erased from the nameplate. He set Brazil's capitalization at a suspiciously low $60,000 for a railroad intended to span 165 miles. Holman had learned a lesson from Markle. This time he advertised that $50,000 in subscriptions were already taken. The Brazil's most noteworthy attribute was a name that few newsmen got right. In reporting of the grand opening of the railroad's portfolio, an Indianapolis newspaper bobbled its name into Fort Wayne, Warsaw & Brazil, and for the next month, copycat wire service stories circulated before this was sorted out, somewhat. In the future, the press occasionally still called it by its predecessor's name, as well as Fort Wayne, Markle & Brazil. If this was not enough, a likewise fraudulent stack of parchments called Fort Wayne & Terre Haute had come out of nowhere in mid-1879. FW&TH was a near second doppleganger itself. It's planned route blurred indistinguishably with the Brazil's, although it branded itself as an honest bunch of boys who would rather die than take a government hand out. Thus, there is nothing further to report about FW&TH. So, here he was pushing a railroad that duplicated both his own lately vacated scheme as well as an already extant giant nemesis. What was he thinking? Could Holman have found a loophole in Indiana law that would have allowed the Brazil to take on the assets, but not the liabilities from the Markle?* Or did he freelance the assets transfer from left pocket to right, discarding his liabilities in the process? Certainly the new incorporation makes little sense unless it was a move to stiff his creditors. Holman probably allowed the owners of worthless Markel's stock for equally worthless Brazil certificates. * This leads to a compelling series of existential questions. Could a guy incorporated as two separate companies legally reach into, say, his right pocket with his left hand? Must the two companies have a shared-use agreement? Which one gets to name the children? |

||||||||||

|

Following the initial hoopla, Holman went underground, for almost nothing was heard from, or about, the Brazil for two years, although it was common knowledge that he was still in active pursuit of prospects. Towards the end of Holman's long silence in early 1881, the editor of the Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel finally asked the question out loud about which so many people had been wondering - Why not terminate the Brazil at Warren, now that the Toledo narrow gauge had built almost to Terre Haute? Time had moved quickly around Holman. There was now talk the the Toledo road - Toledo, Delphos & Burlington might join a consortium of aggressively expanding lines to form a continuous three foot gauge route from Ohio to Texas, and perhaps Colorado. In large part, the Brazil was now redundant. Holman understood, but had no answer for the editor. His scheme worked like this. Holman and his trusted officers fanned out along the proposed route, mainly between Fort Wayne and Warren, to obtain "subscriptions of money" for construction. Despite all of the lawsuits that arose from this ploy, it was never explained even in court what consideration Holman proposed to give in return - most likely stock. (He also solicited outright gifts of land and money from the more civic-minded, but that was a different matter.) The subscriber gave a note to Holman, typically secured by a mortgage on real estate, committing to a certain amount of money towards the project. Conveniently for Holman, third-party escrow accounts were little used and less understood at the time. As long as construction progressed, the subscriber would release a percentage of funds each month. (This was much the same arrangement that Holman had proposed to the Warren town council during the Markle's tenure.) Supposedly the subscriber was protected by an agreement claus specifying that payments would only be due during active construction. If construction stopped, so did payments. Once the railroad was completed, Holman would return the note and the mortgage. Custom-tailored-to-the-sucker payment plans were also available. Holman could afford to be flexible, because his scheme was, first and foremost, all about obtaining the note. Once he had a note in hand, Holman took a well-worn page out of the traveling salesmen's playbook. In those days, grifters prowled farm country offering everything from plows to pianos to fancy cloth yardage at jaw-dropping low prices, and to boot, they refused to take any money upfront for an order. Instead, the buyers gave the salesman a promissory note which the salesman promised to cash only after the goods arrived. The salesman drove his wagon off the farm down to the nearest cooperating bank to sell the note at a discount. Unscrupulous bankers gobbled up these notes because they had the power and means to force payment. Then, the piano never arrived. Holman sold his notes, and the railroad never arrived. The swindle continued-on unabated without even a hint of construction until January, 1882, when a very peculiar article surfaced in the Fort Wayne Sentinel. It commenced with an inside joke, but rapidly degraded into a parroting of Holman's assertions:

|

||||||||||

|

Some naive unfortunates who encountered the piece likely believed that the Brazil might be a good thing in which to sink some earnings from last fall's harvest, but what they could not know was that The Sentinel was a steadfast Holman ally which was not about to print criticsm that would place it on the wrong side of a powerful extended Indiana family of like political persuasion. It remained silent while other county newspapers published the details of his transgressions. On the other hand, competing papers did not bother to inspect the claims. Investigative reporting (more on this later) was rare in anyone's newspaper in those days. And the buffalos: Had it not been for this gentle needle linking him with the Cattlemen's Association escapade, the best evidence we have suggesting the the two Holman were one-and-the-same is the sheer inanity of the herding scheme. The passage is also the only indication yet encountered that Holman may have had a sense of humor. Maybe some of his father's joviality rubbed off after all. The article was otherwise so complementary that it only could have been a bald-faced attempt at ingratiation , or just as likely, a put-up job originating from Holman. Bad weather forced suspension of construction, such as it was, in late March, but in early April Holman, Weissell and C. Orff told The Sentinel that, "They expect to commence pushing the road through to completion next week." Sure enough, a small crew appeared a month later, engaged in clearing brush off the right-of-way. In terms of Holman's real objectives, however, his novel approach to financing by now had run its course. Newspapers or no, word got around, and settling a multitude of lawsuits presumably had severely depleted his bank account.

From then onward, Holman's two walking-dead doppelgangers only inhabited the the courts. The lengthiest suit began in 1888 and due to the complexity of issues and mistakes in rulings, it was tried three times, not including an appeals trip to the Indiana Supreme Court in 1893. It seems that a fellow named Edwards had unwisely invested $2,000, secured by 100 acres of land, in Holmans' pay-as-we-go scheme. Holman sold the note to a bank clerk named Brickley, who got left holding the bag when the Brazil evaporated. When Brickley sued Edwards for specific performance on the note, the latter argued that, since Holman's illegal corporation had failed to compensate him for the note, Holman, not he, held the liability. The court disagreed, and issued a judgement awarding Brickley $3400 and ordered foreclosure on Edward's land. In essence the judge found that a promise was a promise, no matter what. Adding to the outcome's suspicious nature was Edwards claim that Holman had received the note with the intention of assigning it to one of the richest bankers in Indiana, a man named Hite, who used his Brickley, one of his clerks, as a straw man. The courts acknowledged that the evidence backed-up his claim, but ruled the apparent conspiracy as irrelevant. Money had it privileges. On his part, Holman manage to skirt the proceedings because he had had long ago skipped town in favor of Minneapolis, where he had set up residence in the spring of 1885. Cryptic newspaper coverage suggest that sometime before the move a jilted Brazil stockholder, George W. Gibson (no relation to me) filed suit in Huntington to recover his investment money that disappeared with the railroad. The two men arrived at some sort of accommodation, causing Gibson to withdraw his action, but Holman then fled to Minneapolis without making good on the deal, causing Gibson to reinstate the suit in late summer, now joined by the routinely hands-off state as a co-complainant. Early in 1886, in its judgement, the Indiana Supreme Court held that Holman had falsely claimed that he met the $50,000 subscriptions threshold required for an individual to incorporate a railroad company, noting that, "it appears that the subscriptions were merely simulative, made by persons who neither actually nor apparently able to pay the amount subscribed". This was criminal conspiracy, but nothing was done about it. No evidence has so far come to light showing Holman ever underwent prosecution in criminal court for his smorgasbord of illegal activities over the years. |

||||||||||

|

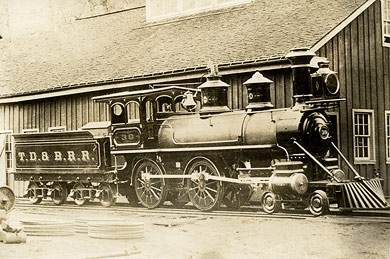

The Fever fizzles But what of the narrow gauge experiment, itself? Holman's 1886 reverse in the courts coincidentally came exactly at the exceedingly brief peak of narrow gauge foment in America, a mere few months before its precipitous collapse. Toledo, Delphos & Burlington did indeed go on to become a critical part of the Ohio-to-Texas association of railroads that came to call themselves the Grand Narrow Gauge Trunk, which ran from Toledo to Houston, with a side route to Cincinnati - although by that time TD&B had been reincorporated as Toledo, Cincinnati & St. Louis. The late historian Prof. George W. Hilton described the TC&StL thus:

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Most slim gauge outfits underwent conversion to either standard gauge or found higher and better use as wheat fields by 1900, but a number of them survived, particularly in Colorado There they found ongoing utility, if not vibrant profitability, once the mines began to give out. Fittingly, the railroad that inspired it all, Denver & Rio Grande, put an end to Continental 48's "grand experiment" an even Century later, still using steam locomotion. About 100 miles of its once-sprawling three foot lines survive as two disconnected tourist operations featuring authentic 1920's era equipment that snail their way through some of the best mountain scenery on the continent, even if one is forced to endure Durango. |

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||