|

Taking Stock of William Jennings Holman and His Improbable Locomotive, Part 2

|

Preface / Table of Contents Part 3: Tunneling Beyond Credulity - |

|||||

|

Peru & Indianapolis Rail Road_ |

||||||

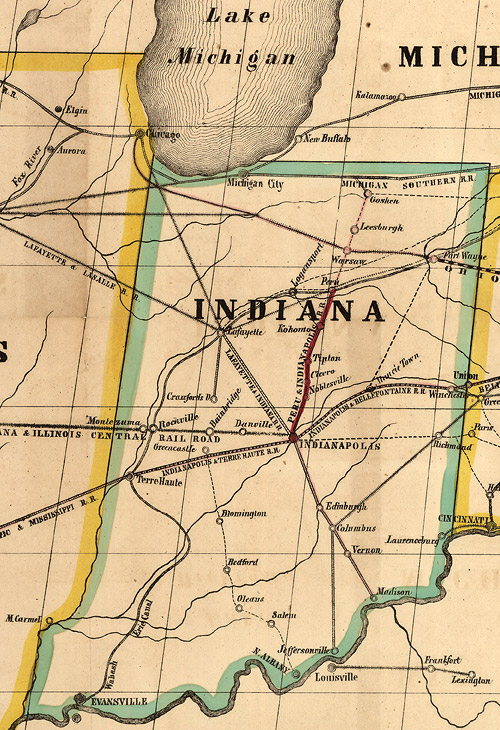

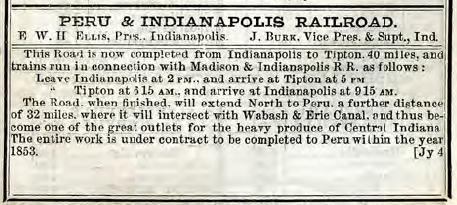

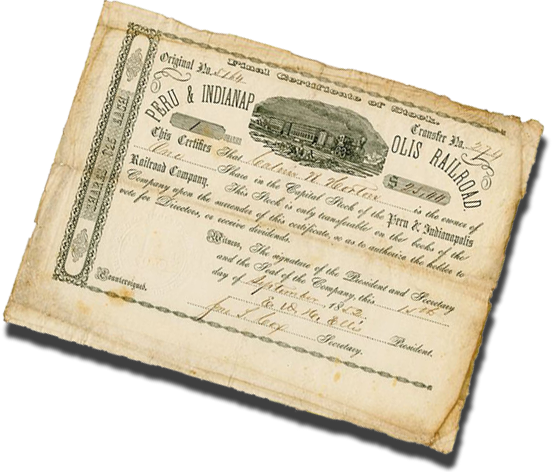

| xxxi | During the period that William Holman worked on the canals, Indiana had only one railroad, Madison and Indianapolis. Its first 17 miles out of Madison opened in 1838, and the line grew by leaps and bounds until it was nearly 400 miles in length by 1847. Otherwise, Indiana was littered with so-called "paper railways", companies whose fundamental rationale for being was in the selling of stocks and bonds, preferrably with only minor largesse-depleting physical work on the right of way. There were many honest attempts, as well, but most frontier railways of both sorts had, at best, only a modest near term reason for existence. Optimism - often blind - that they would bring economic expansion and prosperity was what universally inspired them. But cruel reality of Indiana as a collection of small villages set among virgin forests and occasional swamps meant that it was no place to raise money for a railroad, let alone build one. So, when a group of men, including Holman, decided they would connect Peru (population ~1200) and Indianapolis (population <8,000) with 70 miles of railroad in 1846, they were odds-on destined to fail. The intervening 70 miles in between had only a couple of population centers, diminutive Noblesville (population ~600) and Kokomo, which was no more more than a log county courthouse and a few dozen souls, so the general consensus thereabouts was that the idea was premature. Beyond that, the small businessmen who stood to lose their trade - wagon freighters and tavern (inn) keepers for instance - tended to put out a loud scream whenever the subject of a railroad was broached. Others thought that railroad freight rates would prove to be exorbitant. Some histories claim that the concept of the Peru & Indianapolis Rail Road originated with Holman, which it very well might have been the case, given that he was living in Peru at the time and he had embraced technology while working on the canals. What is certain is that he took on the role as the railroad's chief instigator and booster at age 27. Without Holman, Peru and Indianapolis Rail Road would have remained one of those worthless paper railroads. A 1901 history of line-side Hamilton County proclaimed: Among the most active friends of the road was W. J. Holman, whose untiring perseverance, more than to any one man, is the country indebted for this valuable thoroughfare. When the other men were in despair Holman asserted his belief to be that the road would be built and would be a great benefit to the people of this county. After obtaining a state charter in 1846 and incorporating the following year, there were a host of preliminaries for its founders to address, the most pressing being fundraising, surveying a route and acquiring right-of-way. As a professional civil engineer and member of the board who doubled as its secretary, Holman was intimately involved in all of this. Private individuals formed its original group of subscribers during the first stock offering in April, 1847, but sales receipts fell short of needs, causing the directors to turn to the involved counties for subsidies and continued to press for donations of land for right of way. In the future, stock subscriptions would never mount to very much. Contractors began construction on the 21 miles between Indianapolis and Noblesville sometime during 1848-50 (sources disagree) completed the job in 1851, by which time Holman had also added the title of chief engineer to his resume. Some sources suggest that P&I was Indiana's second operating railroad, but nobody seems to have authoritatively sorted this out. As an old man, Holman boosted himself with the claim that P&I was the state's first railroad, but that was standard Holman claptrap. Physically, P&I was also a shoestring affair that used rail consisting of wooden stringers topped by strap iron bars cast off from Madison & Indianapolis, and it experienced the same shortcomings of iron-topped wooden rail that caused M&I to cast it off to them in the first place. The strap iron had a tendency in hot weather to warp free of the nails intended to hold it in place, which could cause considerable delay to a train while crew members straightened out the problem. Derailments were so numerous that trains carried jacks, wooden blocks and a number of other remedial items with them. Some references say that P&I switched to conventional tee rail for its final 50 miles to Peru, while others claim that it continued using flat iron for the balance. Take your pick.1 Because this part of Indiana was still backwoods country not long ago taken from the natives, P&I led a hand-to-mouth existence until after the Civil War for want of traffic. Madison & Indiana was in the same fix, so - the chronology begins to get a little shaky here - in late summer, 1853, management got the great idea of consolidating their operation with P&I to save on costs. They had been operating P&I using their own employees and equipment from the beginning, so it made sense for them to run both operations as a cost-saving measure. Once the arrangement was agreed upon, they showed Holman the door. Holman immediately found other work. But M&I management had not done their homework and assumed that most of P&I's financial problems centered around Holman's incompetence as a manager. Be that as it may, they had not studied the books sufficiently to realize that under Holman, P&I had only managed to raise $262,000 in stock subscriptions, slightly more than a third of its ultimate cost of construction. Those funds, and what had been scraped from local governments, was already spent, yet work on the section between Indy and Peru remained unfinished. When the railroad was finally completed in the spring, M&I was forced to mortgage P&I for $500,000 to pay off its undoubtedly anxious contractor. And then there was the matter of that strap iron rail on the older portion of the line, which was now totally worn out. The $700,000 cost of replacing it with tee rail broke the bank. P&I went bankrupt, forcing M&I to relinquish control after only eight months. After getting the boot, Holman still had one matter to settle with Madison & Indianapolis. Back in 1852, as a condition of granting a subsidy, Howard County had required Holman and the other officers to post bonds as insurance against any defalcations that they might commit. Holman's bond was a hefty $4,000 (~ $136K in 2021), well beyond his means, so Joseph footed the bill using borrowed the money from a banker friend. Now that the road was finished, the Holmans were due back their money, but M&I somehow wound up with the refund, which it steadfastly refused to hand over with the justification that W. J.'s mismanagement had driven his railroad into bankruptcy. Naturally enough, he sued, arguing both that the refund was contingent upon successful completion of the road, and that the bankruptcy had not occurred while he was in charge of the railway. He won, but the banker never got his money back.

1. A piece of strap iron that separated from the wooden rail was known as a "deadhead", because at speed it could, and occasionally did, penetrate up through a coach or caboose floor with the potential to do skewer whatever hapless soul that got in the way. Somehow the term transmogrified to mean a non-revenue repositioning move of either personnel or equipment. A deadheading engine crew might "ride the cushions" in a passenger train coach on their way home from an outlying location, if unneeded to perform work. Today Deadhead has further mutated to become a proper nown describing a Grateful Dead groupie. |

|

||||