52 Years in the Shops

The life, stories and photos of railfan / SP railroader Frederick Price Boland

|

|

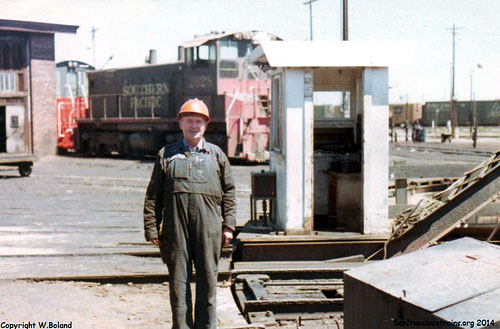

Fred's last day on the job in 1980, standing next to his last assignment, switcher 2266.

His first engine was 2-8-0 #2762 in 1928.

|

It is no secret in the railroad world that the people who deserved the most glory often received the least. For every engineer who through skill and daring brought the Limited in on time, there were hundreds of employees in scores of crafts who daily labored unnoticed to produce this end. The workers in roundhouses and shops were among these, short-changed from the limelight because they practiced their skills in the dim light behind massive brick walls that hid them from the outside world. Their skills and sometimes genius lay in the practical matters of repair and maintenance, whose complexities could tax the "brilliance" of a PHD in mechanical engineering. PHD's they were not, just unassuming people who worked in return for a paycheck, expecting and usually getting no more than the personal satisfaction of a job well done.

Fred Boland was one of these men, a Southern Pacific Bayshore Shops machinist who at times literally labored under candle light, not the limelight. Though Fred was surrounded by fellows who, like he, performed their duties with a type of canny intelligence that grew with their advancing decades of service, he was nevertheless unique. Few men had the outright endurance, as did Fred, to serve for 52 years in the harsh environments of railroad shops and roundhouses. Fewer still ever committed their experiences to paper as did Fred, for these men's skills typically resided in the more practical matters of keeping steam locomotives in good order.

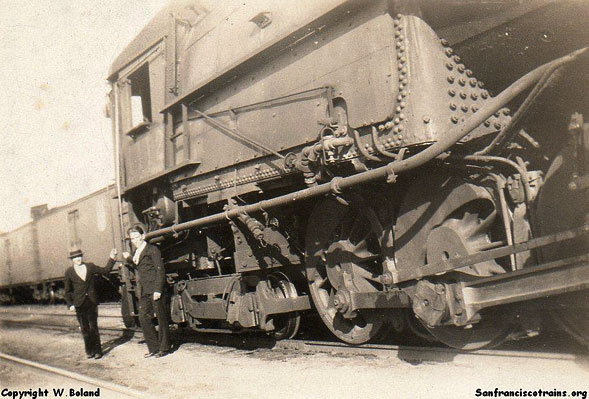

Fred (left) with his best friend, fellow machinist Rudy Hammon. The loco fireman recorded this photo at Roseville. Fred, Rudy and these new Big Malleys (Cab Forwards) were contemporaries, both having entered service in 1929, the year of this photograph. Fred's career lasted more than twice as long as the loco's tenure. Rudy retired from an eventual career as an engineer.

|

But it was not only endurance that kept Fred working all of those years, for Fred enjoyed his job and held a lifelong love of railroading in general. From his earliest days, trains influenced his life. Frederick Price Boland's first home, where he was born on September 18, 1910, was a modest affair next to the Southern Pacific tracks in Crow's Landing, near Modesto, California. From the porch he and his younger brother and sister saw the daily parade of locomotives and cars that reinforced the grip that railroads held on everyone's lives back then. Fred's father, Archie, who originally hailed from Humboldt County, owned a lumber yard and was prosperous enough to provide the kids with an obligatory-for-the-times toy train set. Fred's interest in railroading flowered in his mid-teens. His father closed his lumber yard and moved the family first to San Jose, then in 1924 to Oakland, where he found employment with Blackman Lumber Co. Fred built extensive garden railways, featuring homemade wooden cars and locomotives, in both his San Jose and Oakland backyards. In about 1928, he used his machining skills to construct a large scale model of an SP Cab Forward, and a live steam powered consolidation came soon thereafter. He also began taking photos of trains, this at a time when railfans were almost unheard of.

Perhaps the Oakland move was due to the health of Edna, Fred's mom. She suffered from diabetes, and the disease soon took her life, three days before his eighteenth birthday in 1928. The funeral took place on his birthday .

If it was not for the premature passing of Edna, on the eve of the Depression, Fred may never have worked for the railroad. In a moment of distraught at his mother's funeral, which took place on his 18th birthday, Fred confided to his Uncle Walter Clinton, Edna's brother, that he was worried because he was now going to be partly responsible for supporting his siblings, and he did not have a job. Was there anything that he could do for the railroad, he inquired? Uncle Walter, the head of SP's signal department, was aware that Fred had learned the machinist's trade while attending McClymonds (technical) High School in Oakland and told the boy, "Don't worry Fred. You just go down to the roundhouse Monday. They'll have a job for you."

Early Monday morning, Fred found the roundhouse foreman, but because Fred was a shy type, he didn't think to drop his Uncle's name, and instead asked the foreman if he had any jobs. In typical railroad cultural fashion, the foreman dismissed him with, "Hell no, kid! We ain't got any jobs. Get outta here!" Fred meekly said "thank you" and turned away. After a few steps, he heard, "Hey kid! Are you Fred Boland?" Yes sir. "Come on! We've got a job for you."

Due to his high school training, and perhaps the influence of his Uncle, Fred was able to skip lesser jobs and hire-on as a apprentice machinist. Before the Depression hit, Fred managed to bid-in a job as a locomotive fireman, and later reminisced that he fired a "few Atlantics" before it was discovered that he was underage for the position. Not long afterwards, his uncle lost his job due to political infighting in the front office. For five or six years after the Depression's onset, Fred was forced to get by on meager earnings, because he was furloughed much of each year.

With the lean years behind him, Fred settled into the machinist job that was his life's work. He never got around to finishing his live steamer, but continued with his photography. Railroading could be an insular life, because it could take decades for a worker to build-up enough seniority to work regularly during daylight hours. Railroad lives typically just didn't jive with those of people on the outside, and their love lives correspondingly suffered, doubly so because many women realized how a husband's irregular working hours could make a mess of normal family life. Whatever the case, Fred did not marry until fairly late in life. In June, 1949 he tied the knot with Geraldine "Gerry" Cutsinger, who was ten years his junior. Gerry eventually gave birth to three children, Walter, John and Katherine. Walter took up his father's love of railroading at a young age.

|

|

|

|

|

|

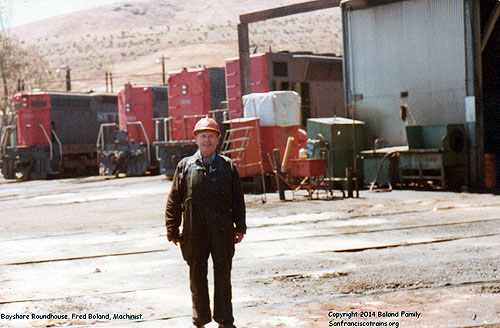

(above & below) Fred in front of Bayshore Roundhouse and turntable, ca. 1972

|

By the time steam was through in the mid-1950's, Fred was one of the senior men in the Bayshore Backshop, thus able to weather the massive rounds of layoffs of men who were no longer needed to maintain those labor-intensive beasts. Fred continued-on in the backshop, now with the diesels. In the early 1960's, the company began consolidating its locomotive maintenance in a few large facilities, and the Bayshore backshop, a comparatively modest operation, was one of the candidates for closure. A violent storm in the Winter of 1962-63 ripped off a large portion of the erecting shop, sealing the deal - SP closed the entire facility soon thereafter (see: The Winds of Change Close Bayshore's Locomotive Backshop).

Fred bid over to the neighboring roundhouse, where he remained until company rules forced him to retire on his 70th birthday, in 1980. It was time, anyway. Son Walter described his waning railroad years this way:

In 1978 a shelf fell over on him. Sometime in the 70’s, the Store Dept. had been moved from its traditional large yellow building into stall 24 to 28 or so of the roundhouse. While the SP could never prove it, dad as well as several men near the incident swore someone pushed the shelf over on him. He had been receiving “retire or else” threats for a while, and I suspect someone actually carried one out. Anyway, dad did not believe in doctors. He had a few of the men carry him home, and place him in bed. Well, mom had a fit when she came home, and pestered him to no end to go see a doctor. When he did, they found out he had Diabetes. So, until he got his blood sugar under control he was on Insulin. Of course, as soon as he did, out went the Insulin. He walked with quite a limp from then on, having done damage to his leg. About oh, 12-14 months before retirement, he was caught red handed sitting in the cab of a locomotive reading the paper. He was brought to a hearing, but fortunately, most of the officials facing him had been apprentices of his. It turned out, the family found out several years later, that was his first heart attack. He faked reading the paper so as to not have to admit to the SP he had an attack. Sorta like “death before quitting”, eh? And, luckily for him, his former apprentices let him go with a warning.

When Fred pulled the pin, Bayshore's roundhouse and yards were on short time themselves, victims of a changing economy and further company consolidation of facilities. Within a couple of years, the roundhouse would close, followed awhile later by the yard itself. His timing was impeccable, but he did not know this. When Fred came home after his retirement party (link), Walter met him at the door with, "How do you like retirement?" to which his dad responded glumly, "I don't. I want more railroad work."

After he retired, several museums attempted to enlist Fred in their restoration projects. He demurred upon each approach with the shallow excuse that working for some small "pike" would not be worthwhile. In truth, he knew that his health stood in the way of such activities. Railroad shops were no health clubs, and his long years of service had taken their toll. A second heart attack came while he attended church in September, 1983, alerting the family to his true condition. On November 6th the next year, a final heart attack, coupled with a stroke, hit him at home late at night. He passed on December 8th in a San Leandro convalescent hospital.

His stories and photos remain.

|

|

Fred and a relative newcomer to SP, 1984

|

Personal stories

- The Winds of Change Close Bayshore's Loco Backshop Accounts of the Shops closure in 1962 by Fred and son Walter

- The Key System Ferryboat "Peralta", 1923-33

- Railroad Whistles & McClymonds High, 1920's

- The Saga of the 4355, 1928-1935

- The Early Steam Days, 1929

- Shorty and His Marmon, ca. 1929

- Power Reverses and Robert Finsterbush, 1929-WWII

- The Tonopah Express, 1929-1927

- I Avoid Cremation, 1931

- The Last Boat of the Night, 1930's

- Depression Era Machine Shop Ramblings

- Big Willy, 1935

- The 4321, 1938

- Working by Candlelight, 1934

- WT Mercier and Mac McCarthy, 1944

- Stories From The Old Shop Phone System, WWII

- The Booster That Ran Backwards, WWII

- When the Mallet Hit The Goat, 1948

- General Foreman Hines, ca. 1955

- Replacing The FM Trainmasters, 1954-1974

- The Winds of Change Close Bayshore's Loco Backshop Accounts of the closing by Fred and son Walter, 1962

- Communication Signals, 1974

|

|

Fred Boland marked his 52 years on the railroad with a collection of stories (above right) that provide a unique insight into an arcane world that is otherwise lightly recorded and understood. While his photos (below), taken with inexpensive cameras, may not be prime examples of the photographers art, the older ones tend to have a quality about them that replicates the inexact recall of dreams or long-ago memories. In the process of viewing them, one almost adopts them into one's own past. Fred also rescued well over a hundred SP steam loco & other blueprints from the Bayshore dumpster in 1958, after steam operations ended. These "company secrets, as his foreman called them, are all online here.

|

|

All that you see here comes from the generosity of Fred's son, Walter, who is a fan as was his father. Walter is a very active volunteer for San Francisco Trains, a small group of amateur and professional rails who are striving to keep the memory of Bayshore Yard and Shops alive through the preservation of its old roundhouse. Another of their worthy projects is the restoration of an 0-6-0 steam engine that once ran along San Francisco's Embarcadero, State Belt Railroad #4.

|

|